Li'l Abner

In today's article, we will explore in depth the fascinating world of Li'l Abner. From its origins to its impact on modern society, we will dive into a variety of aspects related to this topic. We will analyze its implications in culture, economy and politics, as well as its role in people's daily lives. Through expert interviews, case studies, and statistical data, we will offer a complete and balanced view of Li'l Abner, hoping to provide our readers with a clear and deep understanding of this phenomenon. Without a doubt, Li'l Abner is a topic that will not leave anyone indifferent, and we are excited to be able to share with you everything we have discovered about it.

| Li'l Abner | |

|---|---|

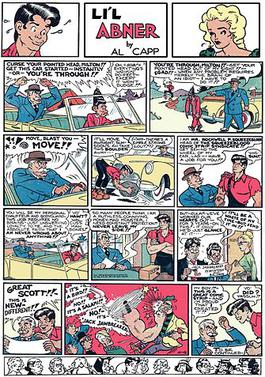

"It's Jack Jawbreaker!" Li'l Abner visits the corrupt Squeezeblood comic strip syndicate in a classic Sunday continuity from October 12, 1947. | |

| Author(s) | Al Capp |

| Current status/schedule | Concluded |

| Launch date | August 13, 1934 |

| End date | November 13, 1977 |

| Syndicate(s) | United Feature Syndicate (1934–1964) Chicago Tribune New York News Syndicate (1964–1977) |

| Publisher(s) | Simon & Schuster, HRW, Kitchen Sink Press, Dark Horse, The Library of American Comics |

| Genre(s) | Humor, satire, politics |

Li'l Abner was a satirical American comic strip that appeared in multiple newspapers in the United States, Canada, and Europe. It featured a fictional clan of hillbillies living in the impoverished fictional mountain village of Dogpatch, USA. Written and illustrated by Al Capp (1909–1979), the strip ran for 43 years, from August 13, 1934, through November 13, 1977.[1][2][3] The Sunday page debuted on February 24, 1935, six months after the daily.[4] It was originally distributed by United Feature Syndicate and later by the Chicago Tribune New York News Syndicate.

Before Capp introduced Li'l Abner, his comic strips typically dealt with northern urban American experiences. However, Li'l Abner was his first strip based in the Southern United States. The comic strip had 60 million readers in over 900 American newspapers and 100 foreign papers across 28 countries.

Characters

Main characters

- Li'l Abner Yokum: Abner is portrayed as a simple-minded, gullible, and sweet-natured country bumpkin. He is 6 feet 3 inches (1.91 m) tall and perpetually 19 years old. He lives in a ramshackle log cabin with his parents. Capp derived the surname "Yokum" as a combination of "yokel" and "hokum".[5][6] Abner represents the archetype of a Candide — a paragon of innocence in a sardonically dark and cynical world.[7] Abner has no consistent profession but was a "crescent cutter" for the Little Wonder Privy Company and later a "mattress tester" for the Stunned Ox Mattress Company. In one post-World War II storyline, Abner became a US Air Force bodyguard of Steve Cantor (a parody of Steve Canyon) against the evil bald female spy Jewell Brynner (a parody of actor Yul Brynner).[8] Early in the strip's history, Abner's primary goal was evading the marital designs of Daisy Mae, the virtuous, voluptuous, barefoot scion of the Yokums' blood feud enemies: the Scraggs. When Capp finally gave in to reader pressure after 18 years and allowed the couple to tie the knot, it was a major media event, even making the cover of Life magazine on March 31, 1952 — with an article titled "It's Hideously True!! The Creator of Li'l Abner Tells Why His Hero Is (SOB!) Wed!!"

- Daisy Mae Yokum (née Scragg): Daisy Mae is hopelessly in love with Abner throughout the entire 43-year run of the comic strip. During most of the run, the dense Abner exhibited little romantic interest in her. She is curvaceous and sports a famous polka dot peasant blouse and cropped skirt.[9] In 1952, Abner reluctantly proposes to Daisy to emulate the engagement of his comic strip ideal, Fearless Fosdick. Fosdick's wedding to longtime fiancée Prudence Pimpleton turns out to be a dream — but Abner and Daisy's ceremony, performed by Marryin' Sam, is binding. Abner and Daisy Mae's nuptials were a major source of media attention, landing them on the aforementioned cover of Life magazine's March 31, 1952, issue.[10] Once married, Abner becomes relatively domesticated. Like Mammy Yokum and the other women in Dogpatch, Daisy Mae does all the work, domestic and otherwise — while the men generally do nothing whatsoever.[11]

- Mammy Yokum: Born Pansy Hunks, Mammy, Abner's mother, is the scrawny, highly principled society leader and bare-knuckle champion of the town of Dogpatch. She married Pappy Yokum in 1902; they produced two sons twice their own size. Mammy dominates the Yokum clan through the force of her personality and dominates everyone else with her fearsome right uppercut (sometimes known as her "Goodnight, Irene" punch), which helps her uphold law, order and decency. She is consistently the toughest character throughout Li'l Abner. Mammy does all the household chores and provides her charges with no fewer than eight meals a day of pork chops and turnips (as well as local Dogpatch delicacies like "candied catfish eyeballs" and "trashbean soup"). Her authority is unquestioned, and her characteristic phrase, "Ah has spoken!", signaled the end of all discussion. Her most familiar phrase, however, is "Good is better than evil becuz it's nicer!" Upon his retirement in 1977, Capp declared Mammy to be his personal favorite of all his characters. She is the only character capable of defeating Abner in hand-to-hand combat.

- Pappy Yokum: Born Lucifer Ornamental Yokum, Pappy is the patriarch of a family. Pappy is so lazy and ineffectual he doesn't even bathe himself. Mammy is regularly seen scrubbing Pappy in an outdoor oak tub ("Once a month, rain or shine"). Ironing Pappy's trousers falls under her purview as well, although she doesn't bother to wait for Pappy to remove them first.[12] Pappy is dull-witted and gullible (in one story he is conned by Marryin' Sam into buying vanishing cream because he thinks it makes him invisible and he picks a fight with his nemesis Earthquake McGoon), but not completely without guile. He had a predilection for snitching "preserved turnips" and smoking corn silk behind the woodshed — Mammy catches him doing so, much to his chagrin. After his lower wisdom teeth grow so long that they squeeze his cerebral Goodness Gland and emerge as forehead horns, he proves himself capable of evil. Mammy solves the problem with a tooth extraction.

- Honest Abe Yokum: Li'l Abner and Daisy Mae's son is born in 1953 "after a pregnancy that ambled on so long that readers began sending me medical books", wrote Capp. Initially known as "Mysterious Yokum" (there was even an Ideal doll marketed under this name) due to a debate regarding his gender (he is stuck in a pants-shaped stovepipe for the first six weeks), he is renamed "Honest Abe" (after President Abraham Lincoln) to thwart his early tendency to steal.[13] His first words are "po'k chop", and they remain his favorite food. Though his uncle Tiny is perpetually frozen at 151⁄2 years old, Honest Abe gradually grows from infant to grade school age and looks very much like Washable Jones — the star of Capp's early "topper" strip. He eventually acquires a couple of supporting character friends for his own semi-regularly featured adventures in the strip. In one story, he lives up to his nickname when there is a nationwide search for a pair of socks sewn by Betsy Ross; after finding that his father is their current owner and is preparing to trade them for the reward (a handshake from the President of the United States), Abe confesses that they are not his to give.

- Tiny Yokum: "Tiny" is an ironic misnomer; Li'l Abner's kid brother remains perpetually innocent and 151⁄2 years old — despite being 7-foot (2.1 m) tall. Tiny is unmentioned in the strip until September 1954, when a relative who has been raising him reminds Mammy that she'd given birth to a second child while visiting her 15 years earlier. (The relative explains that she would have dropped him off sooner, but waited until she happened to be in the neighborhood.) Capp introduced Tiny to fill the bachelor role played for nearly two decades by Li'l Abner, until his 1952 marriage threw the dynamic of the strip out of whack for a period.[14] Pursued by local lovelies Hopeful Mudd and Boyless Bailey, Tiny is even dumber and more awkward than Abner. Tiny initially sports a bulbous nose like both of his parents, but eventually, (through a plot contrivance) he is given a nose job, and his shaggy blond hair is buzz cut to make him more appealing.

- Salomey: The Yokums' beloved pet pig. Her moniker is a pun on salami and Salome. Cute, lovable and intelligent (arguably smarter than Abner, Tiny or Pappy), she is accepted as part of the family ("the youngest", as Mammy introduces her). Gourmet experts claim she is an insanely valuable 100% "Hammus alabammus" — a fictional species of pig, and the last female known in existence. A plump, juicy Hammus alabammus is the rarest and most vital ingredient of "ecstasy sauce", an indescribably delicious gourmet delicacy. Consequently, Salomey is frequently targeted by unscrupulous sportsmen, hog breeders and gourmands (like J.R. Fangsley and Bounder J. Roundheels), as well as wild boars (such as Boar Scarloff and Porknoy).

Supporting characters and villains

- Marryin' Sam: A traveling preacher (by mule) who specializes in $2 weddings. He also offers the $8 "ultra-deluxe" special, a ceremony which he officiates while being drawn and quartered by four rampaging jackasses. He cleans up once a year — during Sadie Hawkins season when bachelors are dragged to the altar by their prospective brides.[15] Sam, whose face and figure were reportedly modeled after New York City mayor Fiorello LaGuardia,[16] starts out as a stock villain but gradually softens into a genial, opportunistic comic foil. He isn't above chicanery to achieve his ends and is warily viewed by Dogpatch men as a traitor to his gender. Sam was prominently featured on the cover of Life in 1952 when he presided over the wedding of Li'l Abner and Daisy Mae. In the 1956 Li'l Abner Broadway musical and 1959 Li'l Abner film adaptation, Sam is played by actor Stubby Kaye.

- Moonbeam McSwine: The unwashed but curvy Moonbeam is one of the iconic hallmarks of Li'l Abner — an unkempt, lazy, corncob pipe-smoking, flagrant (and fragrant), raven-haired, earthly (and earthy) woman. Beautiful Moonbeam prefers the company of pigs to suitors — much to the frustration of her equally lazy father, Moonshine McSwine. She is usually showcased luxuriating among the hogs, somewhat removed from the main action of the story, in a deliberate parody of glamour magazines and pinup calendars of the day. Capp designed her in a caricature of his wife Catherine, who had also suggested Daisy Mae's name. In one comic, it is revealed that she bears a striking resemblance to Gloria Van Welbuilt, a famous socialite. She is generally portrayed as good-natured and kind, as shown when she runs to Dogpatch carrying two shmoos under her arms to save them from going extinct, wondering if humanity would ever be good enough for them. She also tells Abner to stop worrying about being a father. Moonbeam seems to have an interest in romance as in some strips, she is seen flirting with and even kissing various male characters, including Abner. She once expresses the desire to have a family of her own and discusses the matter of trapping a husband with Abner. In one strip, it is revealed that Moonbeam was in love with Abner when they were children. In the same strip, it is shown that Moonbeam's disposition for filth was born out of a failure to understand Abner's interests when he was a child. She actually disliked hogs as a child, but after seeing Abner ignoring the openly romantic advances of a clean Daisy Mae, she dived headfirst into a mud hole where some hogs were wallowing to earn his love, believing that if Abner didn't like clean girls, he must like them dirty. Much to her disappointment, this failed to capture his attention. Moonbeam is also unknowingly the star of a horror movie directed by Rock Pincus, head film director of a species called the Pincushions, from planet Pincus 7. This venture ends when Rock is unknowingly grilled, put into a hot dog bun and devoured while still alive.

- Hairless Joe and Lonesome Polecat: The inseparable, cave-dwelling purveyors of "Kickapoo Joy Juice" — a moonshine elixir of such potency that the fumes alone have been known to melt the rivets off battleships, possibly inspired by a real patent medicine named "Kickapoo Indian Sagwa" although it was produced in Connecticut.[17] Concocted in a large wooden vat by Lonesome Polecat (of the "Fried Dog" Indian tribe, later known as the Polecats, "the one tribe who have never been conquered") and Hairless Joe (a hirsute, club-wielding, modern Cro-Magnon who frequently makes good on his oft-repeated threat, "Ah'll bash yore haid in!") The ingredients of the brew are both mysterious and all-encompassing[18] (much like the contents of their cave, which has been known to harbor prehistoric monsters). When a batch "needs more body", the pair simply go out and club one (often a moose), and toss it in. Over the years, the "recipe" has called for live grizzly bears, panthers, kerosene, horseshoes, and anvils, among other ingredients. An officially licensed soft drink called Kickapoo Joy Juice is still produced by the Monarch Beverage Company of Atlanta, Georgia. Lonesome Polecat was also the official team mascot of the Sioux City Soos, a former Minor League baseball franchise of Sioux City, Iowa.[19][20]

- Joe Btfsplk: The world's worst jinx, Joe Btfsplk has a perpetually dark rain cloud over his head. Instantaneous bad luck befalls anyone in his vicinity. Though well-meaning and friendly, his reputation inevitably precedes him, so he is lonely and thus associates himself with the Scraggs, except in World War II when Joe decides to associate himself with Hirohito. He has an apparently unpronounceable name, but creator Al Capp "pronounced" Btfsplk by simply blowing a "raspberry", or Bronx cheer.[21] Joe's personal storm cloud became one of the most iconic images from the strip.

- Senator Jack S. Phogbound: His name is a variant of "jackass", as made plain in his campaign slogan (see Dialogue and catchphrases). The senator was Al Capp's parody of a blustering, self-serving Southern politician. Before 1947, Phogbound was known as Fogbound, but in that year Phogbound "blackmails his fellow Washington senators to appropriate two million dollars to establish Phogbound University" and its brass statue of Phogbound, both reminiscent of self-aggrandizements by Huey Long;[22] the name change allowed Capp to call the university P.U.[23] Phogbound is a corrupt, conspiratorial blowhard; he often wears a coonskin cap and carries an old fashioned flintlock rifle to impress his gullible constituents. In one sequence, Phogbound is unable to campaign in Dogpatch, so he sends his aides with an old, hot-air-filled gas bag that resembles him, and nobody notices the difference.

- Available Jones: An avaricious entrepreneur always available for a price. He has many side businesses, including minding babies ("Dry" for 5¢, "Other kinds" for 10¢). He provides anything from safety pins to battleships, but his most famous "provision" is his cousin, Stupefyin' Jones.

- Stupefyin' Jones: A walking aphrodisiac, Stupefyin' is so gorgeous that any man who glimpses her freezes in his tracks and is rooted to the spot. While she is generally favored by the men of Dogpatch, she is dangerous for a confirmed bachelor to encounter on Sadie Hawkins Day. Actress Julie Newmar became famous overnight for playing the role in the 1956 Li'l Abner Broadway musical (and the 1959 film adaptation) without a single line.[24]

- General Bullmoose: Created by Al Capp in June 1953, Bashington T. Bullmoose is a mercenary, cold-blooded, capitalist tyrant tycoon. Bullmoose's motto (see Dialogue and catchphrases) was adapted by Capp from a statement made by Charles E. Wilson, the former head of General Motors when it was America's largest corporation. In 1952, Wilson told a Senate subcommittee, "What is good for the country is good for General Motors, and vice-versa." Wilson later served as United States Secretary of Defense under President Dwight D. Eisenhower.[25] Bullmoose had a boyhood dream to possess all the money in the world – which he nearly achieved, as Bullmoose Industries owns or controls all businesses in Dogpatch. He has a milquetoast son named Weakfish, and is sometimes accompanied by his "secretary", Bim Bovak (whose name was a pun on the term "bimbo" and bombshell actress Kim Novak). Li'l Abner becomes embroiled in many globetrotting adventures with Bullmoose over the years. Despite his adamantine exterior, General Bullmoose is capable of a kind of capitalist gallantry. "Those Slobbovians have done me out of a hundred thousand dollars!" he once exclaimed, after falling victim to fraud. "Nearly an hour's income, bless 'em!"

- Wolf Gal: A feral Amazonian beauty who was raised by wolves and prefers to live among them; she lures unwary Dogpatchers to feed her ravenous pack. Wolf Gal is possibly a cannibal, but the point is never stressed since she considers herself an animal, as do the rest of Dogpatch. One of Capp's more popular villains, Wolf Gal was briefly merchandised in the fifties with her own comic book, doll, hand puppet, and latex Halloween mask.

- Earthquake McGoon: Billing himself as "the world's dirtiest wrassler", the bearded, bloated McGoon first appears in Li'l Abner as a traveling exhibition wrestler in the late 1930s, and was reportedly partially based on real-life grappler Man Mountain Dean. He has a look-alike cousin named Typhoon McGoon. McGoon became increasingly prominent in the Li'l Abner Cream of Wheat print ads of the 1940s, and later, with the early television exposure of wrestlers such as Gorgeous George.[26] Earthquake is the nastiest resident of neighboring Skonk Hollow — a notoriously lawless community where no Dogpatcher dares set foot. McGoon often attempts to walk Daisy Mae home "Skonk Hollow style", the implications of which are never made specific.

- The Scraggs: Hulking, leering, gap-toothed twin miscreants Lem and Luke and their proud father, Romeo. Apelike and gleefully homicidal, the evil Scraggs were officially declared inhuman by an act of Congress, and pass the time by burning down orphanages just to have light to read by (although they quickly remember that they are illiterate). Distant kinfolk of Daisy Mae, they carry on a blood feud with the Yokums throughout the run of the strip; in their first introduction after being run out of a Kentucky county at gunpoint, they try to kill Li'l Abner but are beaten up by both Abner and Mammy Yokum. Mammy then banishes the Scraggs to Skonk Hollow with a dividing line between Skonk Hollow and Dogpatch, with the understanding that although the Scraggs can't cross the line, any member of Dogpatch who does cross becomes their prey. A long-lost kid sister, named "*@!!*!"-Belle Scragg, briefly joins the clan in 1947. Attired in a prison-striped reform school miniskirt, "*@!!*!"-Belle is outwardly attractive but as rotten as her siblings on the inside. Her censored first name is an expletive, compelling everyone who addresses her to apologize profusely afterwards.

- Nightmare Alice: Dogpatch's own "conjurin' woman", a hideous, cackling crone who practices Louisiana Voodoo and black magic. Capp named her after the carnival-themed horror film, Nightmare Alley (1947). She employs witchcraft to "whomp up" ghosts and monsters to do her bidding. She is occasionally assisted by Doctor Babaloo, a witch doctor of the Belgian Congo, as well as her demonic niece Scary Lou, who specializes in hexing voodoo dolls that resemble Li'l Abner.

- Ole Man Mose: The mysterious Mose is reportedly hundreds of years old, and lives like a hermit in a cave atop a mountain, refusing to "kick the bucket", which is positioned just outside his cave door. His wisdom is absolute ("Ole Man Mose — he knows!"), and his sought-after annual Sadie Hawkins Day predictions — though cryptic and misleading — are 100% accurate.

- Evil Eye Fleagle: Fleagle has a unique skill: the evil eye. A "whammy", as he calls it, can stop a charging bull in its tracks. A "double whammy" can fell a skyscraper, leaving Fleagle exhausted. His dreaded "triple whammy" can melt a battleship but would practically kill Fleagle in the process.[27] The zoot suit-clad Fleagle is a native of Brooklyn, and his New York accent is unmistakable — especially when addressing his "goil", the zaftig Shoiley. Fleagle was so popular, that licensed plastic replicas of Fleagle's face were produced in the 1950s, to be worn as lapel pins. Battery-operated, the wearer could pull a string and produce a flashing light bulb "whammy". Fleagle was reportedly based on a real-life person, a Runyonesque local boxing trainer and hanger-on named Benjamin "Evil Eye" Finkle. Finkle and his famous "hex" were a ringside fixture in New York boxing circles during the 1930s/40s. Fleagle was portrayed by character actor Al Nesor in the stage play and film.

- J. Roaringham Fatback: The bloated, self-styled "Pork King" is a greedy, unscrupulous business tycoon. Incensed to find that Dogpatch casts a shadow on his breakfast egg, he has the whole community moved for his convenience.

- Gat Garson: Li'l Abner's doppelgänger, a murderous racketeer with an interest in Daisy Mae.

- Aunt Bessie: Mammy's socialite kid sister, the Duchess of Bopshire, and the "white sheep" of the family. Bessie's string of marriages into Boston and Park Avenue aristocracy leave her a classist, condescending snob. Her status-seeking crusades to make Abner over and marry him off into high society are always doomed to failure. Aunt Bessie virtually disappears from the strip after Abner and Daisy Mae's marriage in 1952, having conceded defeat in her attempt to remake Abner in her own image as a social climber.

- Big Barnsmell: The lonely "inside man" at the "Skonk Works" — a dilapidated factory located on the remote outskirts of Dogpatch. Scores of locals are done in yearly by the toxic fumes of concentrated "skonk oil", which is brewed and barreled daily by Barnsmell and his cousin ("outside man" Barney Barnsmell) by grinding dead skunks and worn shoes into a smoldering still, for some unspecified purpose. His job wreaks havoc on his social life ("He has an air about him," as Dogpatchers put it), and the name of his facility entered the modern lexicon via the Lockheed Skunk Works project.

- Soft-Hearted John: Dogpatch's mercenary, black-hearted grocer, the ironically named Soft-Hearted John gleefully swindles and starves his clientele and looks disturbingly satanic. He has an idiot nephew who sometimes runs the store in his stead, named Soft-Headed John.

- Smilin' Zack: A cadaverous, outwardly peaceable mountaineer with a menacing grin and shotgun, who prefers things "quiet" to the point of silence. Zack's moniker is a reference to another comic strip, The Adventures of Smilin' Jack by Zack Mosley.

- Dr. Killmare: The local Dogpatch physician who is a horse doctor. His name is a pun on Dr. Kildare.

- Cap'n Eddie Ricketyback: Decrepit World War I aviator and proprietor/sole operator of the even more decrepit Dogpatch Airlines. Cap'n Eddie's name is a spoof of decorated World War I flying ace, Eddie Rickenbacker. In 1970, Cap'n Eddie and his firm Trans-Dogpatch Airlines are awarded the West Berlin Route by his old rival Count Felix Von Holenhedt.

- Count Felix Von Holenhedt: German flying ace who in 1970 (age 89) is appointed as West German Civil Aviation Chief. He is never photographed without his World War I spiked helmet on his head. He wears it to cover the hole in his head from being shot "clean through th' haid, in a dogfight over Flanders Field in 1918" by Cap'n Eddie Ricketyback. Nonetheless, the two old enemies eventually patch things up; Cap'n Ricketyback persuades the Count to settle in the States. "Jah!" cries the Count. "I got a cousin in Milvaukee!" Von Holenhedt is the only person able to properly play the "pfschlngg", a complexly-shaped brass instrument, part of whose tubing needs to pass through the player's head.

- Weakeyes Yokum: Cousin Weakeyes mistakes grizzly bears for romantically inclined "rich gals" in fur coats, and ends sequences characteristically by walking off a cliff.

- Young Eddie McSkonk and U.S. Mule: The ancient, creaky, white-bearded Dogpatch postmaster and his hoary jackass mount. They are usually too feeble to handle the sacks of timeworn, cobweb-covered letters marked "Rush" at the Dogpatch Express Post Office.

- J. Colossal McGenius: The brilliant marketing consultant and "idea man" who charges $10,000 per word for his sought-after business advice which usually bankrupts his clients. McGenius is given to telling long-winded jokes with forgotten punch lines, as well as for spells of hiccups and belches (borne of a fondness for gassy soft drinks like "Burpsi-Booma" and "Eleven Urp"). He is aided by his lovely and meticulously efficient secretary, Miss Pennypacker.

- Silent Yokum: Prudent Cousin Silent never utters a word unless it's vitally important. Consequently, he hasn't spoken in 40 years. The arrival of Silent in Dogpatch signals earthshaking news on the horizon. Capp would milk readers' suspense by having Silent "warm up" his rusty, creaking jaw muscles for a few days, before the momentous pronouncement.

- Happy Vermin: The "world's smartest cartoonist" — a caricature of Ham Fisher — who hires Li'l Abner to draw his comic strip for him in a dimly-lit closet. Instead of using Vermin's tired characters, Abner peoples the strip with hillbillies. Vermin tells his assistant: "I'm proud of having created these characters!! They'll make millions for me!! And if they do — I'll get you a new light bulb!!"

- Big Stanislouse; aka Big Julius: Stanislouse is a brutal gangster with a childish fondness for TV superheroes (like "Chickensouperman" and "Milton the Masked Martian"). Part of a virtual goon squad of comic mobsters that inhabit Li'l Abner and Fearless Fosdick, the oafish Stanislouse alternates with other all-purpose underworld thugs, including "the Boys from the Syndicate" — Capp's euphemism for The Mob.

- The Square-Eyes Family: Mammy's encounter with these unpopular Dogpatch outcasts first appears in 1956 as a thinly-veiled appeal for racial tolerance. It was later issued as an educational comic book — called Mammy Yokum and the Great Dogpatch Mystery! — by the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith.

- Appassionata Von Climax: One of a series of predatory, sexually aggressive sirens who pursue Li'l Abner prior to his marriage, and even afterward, much to the consternation of Daisy Mae. One of many femmes fatales and spoiled debutantes, including Gloria Van Welbilt, Moonlight Sonata, Mimi Van Pett and "The Tigress"; Appassionata was portrayed by Tina Louise (on stage) and Stella Stevens (on film). Capp was surprised he got her suggestive name past censors.

- Tenderleif Ericson: Discovered frozen in the mud where her Viking ship sank in 1047, Tenderleif is Leif Ericson's beautiful seventeen-year-old sister (complete with breastplate, Viking helmet and Norwegian accent). As soon as she sees Li'l Abner, she starts to warm up and breathe hard, as she hasn't had a date for nine hundred years.

- Princess Minihahaskirt: A Native American princess. One of the several Native women who try to seduce Lonesome Polecat, the including Minnie Mustache, Raving Dove, Little Turkey Wing, and Princess Two Feathers.

- Liddle Noodnik: A naked and miserable resident of perpetually frozen Lower Slobbovia, Liddle Noodnik usually recites a farcical poem to greet visiting dignitaries or sings the Slobbovian national anthem. Like many terms in Li'l Abner, Noodnik's name was derived from Yiddish; Nudnik is a slang term for a bothersome person or pest.

- Pantless Perkins: A late addition to the strip, Pantless Perkins is Honest Abe's brainy friend from a series of kid-friendly stories in the 1970s, probably created to compete with Peanuts. Pantless doesn't own any trousers and wears an oversized turtleneck sweater to hide this fact. In one storyline, he helps Honest Abe find the long-lost lover of a millionaire in return for a pair of pants. Unfortunately, the prospective groom drops dead after tasting the terrible cooking of his bride-to-be, and Pantless remains without pants.

- Rotten Ralphie: The child version of Earthquake McGoon, Ralphie is Dogpatch's neighborhood bully. Exceedingly large for his age, Ralphie always wears a cowboy outfit that is several sizes too small. In one storyline, after Ralphie beats up every boy in Dogpatch at the same time, Pantless Perkins and Honest Abe trick him into getting into a fight with the Scragg boys of Skonk Hollow, who beat him up.

- Marcia Perkins: An outwardly normal teenager whose lips give off 451 °F of electromagnetic heat, frying the brain of any boy who kisses her. Declared a walking health hazard, Marcia wears a public warning sign ("Do Not Kiss This Girl, by Order of the Dept. of Health, Education and Welfare"). Her notoriety precedes her everywhere except in Dogpatch, where she meets and falls for Tiny Yokum.

- Bet-a-Million Bashby: Bashby amasses his colossal fortune by always betting on sure things and betting with fools. However, Abner always wins bets against him through foolish luck.

- The Widder Fruitful: A iconic Dogpatch regular often glimpsed in passing or featured in crowd scenes. The ample widow is always holding three or four naked newborns under each arm carried backside forward, with a large brood of children following behind her.

- Loverboynik: In 1954, Capp sent a letter to Liberace stating his intention to spoof him in Li'l Abner as "Liverachy". Liberace had his lawyers threaten to sue. Capp changed the name and went ahead anyway. Nicknamed the "Sweetheart of the Piano", Loverboynik is a blonde, dimpled pianist and TV heartthrob. According to Capp, Liberace was "cut to the quick" when the parody appeared. Capp insisted that Loverboynik was not Liberace because Loverboynik "could play the piano rather decently and rarely wore black lace underwear."[28]

- Rock Hustler: An unscrupulous publicity agent turned marketing mogul. He masterminds an advertising campaign promoting the miracle diet food "Mockaroni", not disclosing that it's both addictive and lethal: "The more you crave, the more you eat. The more you eat, the thinner you get — until you float away..."

- Dumpington Van Lump: The bloated, almost catatonic heir to the Van Lump fortune, Dumpington can only utter one syllable ("Urp!") until he sees Daisy Mae for the first time. His favorite book is called How to Make Lampshades Out of Your Friends. Capp chose the Dumpington storyline to illustrate his lesson on continuity in storytelling in the Famous Artists Cartoon Course.

- Sam the Centaur: A mythical creature with a chiselled profile and blonde mane. Sam is a Greek centaur who occasionally roams the mountains of Dogpatch instead of the mountains of Thessaly. Available Jones insists that he isn't real.

- Jubilation T. Cornpone: Dogpatch's founder and most famous resident, memorialized by a town statue. He was a Confederate known for "Cornpone's Retreat", "Cornpone's Disaster", "Cornpone's Stupidity", "Cornpone's Misjudgment", "Cornpone's Hoomiliation", and "Cornpone's Final Mistake". Cornpone was such an incompetent military leader that he came to be considered an important asset of the opposing side. According to the Li'l Abner stage play, the statue was commissioned by Abraham Lincoln. In one storyline, the statue is filled with Kickapoo Joy juice, which brings it to life. It then goes on a rampage, beheading all the statues of Union Army generals. The U.S. Army can't destroy it, since it's a National Monument, so Kickapoo Joy Juice is poured into a Union statue, which results in both statues annihilating each other. At Mammy Yokum's urging, the statue pieces are put back together with glue. The general is the namesake of a musical number in the Li'l Abner musical, sung by Marryin' Sam and chorus.

- Jubilation T. Cornpone Jr: The son of General Cornpone. A former commander of army mules, he becomes Commander of all U.N. Forces against Invaders from Outer Space, despite being the most incompetent general of all time. He is given the job because no other general would take it. Cornpone falls in love with Princess Pocahauntingeyes and lives with her in the land above Dogpatch, connected by the "Trashbean stalk".

- Romeo McHaystack: An aspiring Don Juan from Pineapple Junction, whose attempts at romancing women are frustrated because of the Civic Improvement League tattooing a warning about him on his forehead. He decides to go after Dogpatch women when he discovers that radioactive waste is suspended above the town, casting it permanently in darkness.[29]

- Sadie Hawkins: Sadie Hawkins is considered the homeliest girl in Dogpatch. Her father Hekzebiah Hawkins, a prominent Dogpatch resident, does not want Sadie to live at home for the rest of his life, and establishes the first annual Sadie Hawkins Day, a foot race in which all the unmarried women pursued the town's bachelors and get married if they catch them.[30] A pseudo-holiday created in the strip, it's still frequently observed today in the form of Sadie Hawkins dances, where it is customary for women to ask men to dance.

- Lena the Hyena: An ugly Lower Slobbovian girl, initially only glimpsed from the neck down. Lena is so ugly that anyone who sees her is immediately driven insane. After weeks of hiding Lena's face behind "censored" stickers and strategically placed dialogue balloons, Capp invited fans to draw Lena in a nationwide contest in 1946. Lena was ultimately revealed in the winning entry (as judged by Frank Sinatra, Boris Karloff and Salvador Dalí) drawn by cartoonist Basil Wolverton.

- Joanie Phoanie: A communist agitator who sings revolutionary songs about class warfare (with titles like "Molotov Cocktails for Two") while traveling via limousine and charging exorbitant concert fees to impoverished orphans. Joanie is Capp's parody of singer/songwriter Joan Baez. The character caused controversy in 1966, and many newspapers only ran censored versions of the strips. In her autobiography, Baez said about it that "Mr. Capp confused me considerably. I'm sorry he's not alive to read this, it would make him chuckle."[31]

- S.W.I.N.E.: Capp lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, near Harvard, and satirized student political groups and hippies during the Vietnam war protest era, including the Youth International Party (YIP) and Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in Li'l Abner as S.W.I.N.E. (Students Wildly Indignant about Nearly Everything).

- Al Capp claimed that he tried to give minor characters in Li'l Abner names that would render further description unnecessary. This includes recurring characters Tobacco Rhoda, Joan L. Sullivan, Hamfat Gooch, Global McBlimp, Concertino Constipato, Jinx Rasputinburg, J. Sweetbody Goodpants, Reactionary J. Repugnant, B. Fowler McNest, Fleabrain, Stubborn P. Tolliver, Idiot J. Tolliver, Battling McNoodnik, Mayor Dan'l Dawgmeat, Slobberlips McJab, One-Fault Jones, Swami Riva, Olman Riva, Sir Orble Gasse-Payne, Black Rufe, Mickey Looney, "Ironpants" Bailey, Henry Cabbage Cod, Flash Boredom, Priceless and Liceless, Hopeless and Soapless, Disgustin' Jones, Skelton McCloset, Hawg McCall, "Good old" Bedly Damp, and more.

Fearless Fosdick

Fearless Fosdick was a comic strip-within-the-strip parody of Chester Gould's plainclothes detective, Dick Tracy. It first appeared in 1942 and ran intermittently in Li'l Abner over the next 35 years. Gould was also personally parodied in the series as cartoonist Lester Gooch — the small and occasionally deranged creator of Fearless Fosdick. The style of the Fosdick sequences closely mimicked Tracy, including the urban setting, outrageous villains, high mortality rate, hatched shadows, and lettering style — Gould's signature was also parodied. Fosdick battles several archenemies with absurd names like Rattop, Anyface, Bombface, Boldfinger, the Atom Bum, the Chippendale Chair, and Sidney the Crooked Parrot, as well as his own criminal mastermind father, "Fearful" Fosdick (aka "The Original"). Fosdick is perpetually pierced by so many bullets that he resembles Swiss cheese.[32] Fosdick seems impervious and considers the holes "mere scratches", however, and always reports back to his corrupt superior "The Chief" for duty the next day.

Besides being fearless, Fosdick is "pure, underpaid and purposeful," according to his creator. He has notoriously bad aim, often causing collateral damage to pedestrians. Fosdick sees his duty as destroying crime rather than maintaining safety. Fosdick lives in squalor at a dilapidated boarding house run by his mercenary landlord, Mrs. Flintnose. He never marries his fiancée Prudence Pimpleton (despite an engagement of 17 years). He became the star of his own NBC puppet show that same year. Fosdick was the long-running advertising spokesperson for Wildroot Cream-Oil, a popular men's hair product of the period.

Setting and fictitious locales

Although apparently set in the Kentucky mountains, situations often took the characters to different destinations — including New York City, Washington, D.C., Hollywood, the South American Amazon, tropical islands, the Moon, and Mars — as well as some purely fictional locations:

Dogpatch

Including every stereotype of Appalachia, the impoverished Dogpatch consists mostly of ramshackle log cabins, turnip fields, pine trees, and hogwallows. Most Dogpatchers are shiftless, ignorant scoundrels and thieves. The men are too lazy to work, and Dogpatch girls are desperate enough to chase them. Those who farm their turnip fields watch turnip termites swarm by the billions every year to devour Dogpatch's only crop (along with their homes, their livestock, and all their clothing).

The local geography is fluid and complex; Capp continually changes it to suit the current storyline. Natural landmarks include (at various times) Teeterin' Rock, Onneccessary Mountain, Bottomless Canyon, and Kissin' Rock. Local attractions include the West Po'k Chop Railroad; the "Skonk Works", a dilapidated factory located on the remote outskirts of Dogpatch; and the General Jubilation T. Cornpone memorial statue.

In one storyline, Dogpatch's Cannonball Express train, after 1,563 tries, finally delivers its cargo to Dogpatch citizens on October 12, 1946. Receiving a 13-year stack of newspapers, Li'l Abner's family realizes that the Great Depression is happening and that banks will close; they race to take their money out of the bank before realizing they have no money to begin with. Other news from the stack includes the inauguration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt as president on March 4, 1933 (although Mammy Yokum thinks the President is Teddy Roosevelt), and a picture of Germany's new leader Adolf Hitler (April 21, 1933).

Capp intended for suffering Americans in the midst of the Great Depression, to laugh at the residents of Dogpatch even worse off than themselves.[33] In his words, Dogpatch was "an average stone-age community nestled in a bleak valley, between two cheap and uninteresting hills somewhere." Early in the continuity, Capp referred to Dogpatch being in Kentucky, but he was careful afterward to keep its location generic, probably to avoid cancellations from Kentucky newspapers. He then referred to it as Dogpatch, USA, and did not give any specific location. Many states tried to claim ownership of the town (like Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama), yet Capp did not confirm any of these. Dogpatch's distinctive cartoon landscape became as identified with the strip as any of its characters. Later, Capp licensed and was co-owner of an 800-acre (3.2 km2), $35 million theme park called Dogpatch USA near Harrison, Arkansas.

Lower Slobbovia

Frigid, faraway Lower Slobbovia was a political satire of communist nations and foreign diplomacy.[34] Its residents are perpetually waist-deep in several feet of snow, and icicles hang from their frostbitten noses.[35] The favorite dish of the starving natives is raw polar bear. Lower Slobbovians speak with pidgin Russian accents.

Slobbovia is an iceberg, which continually capsizes as its lower portions melt. This dunks Upper Slobbovia into Lower Slobbovia, and raises the latter into the former.

Conceptually based on Siberia, or perhaps specifically on Birobidzhan, the region made its first appearance in Li'l Abner in April 1946. Ruled by Good King Nogoodnik (sometimes known as King Stubbornovsky the Last), the Slobbovian politicians are even more corrupt than their Dogpatch counterparts. Their monetary unit is the "rasbucknik",: one was worth nothing and a large quantity is worth even less, due to the trouble of carrying them around. The local children are read tales from "Ice-sop's Fables", parodies of Aesop's Fables with a dark sardonic bent (and titles like "Coldilocks and the Three Bares").

Other fictional locales

Other fictional locales included Skonk Hollow, El Passionato, Kigmyland, the Republic of Crumbumbo, Lo Kunning, Faminostan, Planets Pincus Number 2 and 7, Pineapple Junction and the Valley of the Shmoon.

Mythic creatures

Li'l Abner features many allegorical animals, designed to satirize a disturbing aspect of human nature. They include:

- Shmoos — Creatures that breed exponentially, consume nothing, and eagerly provide everything that humankind wants. They produce milk (bottled) and eggs (packaged), and taste like pork when roasted, chicken when fried, and steak when broiled.[36]

- Kigmies — Masochistic creatures who loved to be kicked up to a point, after which they go on a rampage of retaliation. (The Kigmy story was originally a metaphor for racial and religious oppression. Capp's surviving preliminary sketches of the Kigmies make this apparent, as detailed in the introductory notes to Li'l Abner Dailies 1949: Volume 15, Kitchen Sink Press, 1992).

- The Bald Iggle — A cute, wide-eyed creature whose gaze compels everyone to involuntarily tell the truth. The Iggle is officially declared a public menace by the FBI and exterminated.

- Nogoodniks — Also known as bad Shmoos.[37] Nogoodniks are sickly green, have small red eyes, sharp yellow teeth, and are the sworn enemies of humanity. Frequently sporting 5 o'clock shadow, eyepatches, scars, and fangs — they devour good Shmoos and wreak havoc on Dogpatch. When they are subjected to George Jessel's recording of Paul Whiteman's "Wagon Wheels", it kills them instantly.

- Shminfants — Modified baby Shmoos, which look like human babies but are eternally young, come in a variety of colors, and never need changing.

- Shtoonks — Imported from the Slobbovian embassy, Shtoonks are sharp-toothed, hairy, flying creatures which are sneaky, smelly, surly, and inedible. Shtoonks love human misery so much that they enjoy bringing bad news. They temporarily replace postage stamps by delivering bills and other bad news for free.

- Mimikniks — Obsessive Slobbovian songbirds who mimic the singing of anyone they hear. (Those who have heard Maria Callas are valued. Those who have heard George Jessel are shot.) The only song they know the words to is Short'nin' Bread, due it being the only record in Lower Slobbovia.

- The Money Ha-Ha — An alien creature from "Planet Pincus No. 2", with ears shaped like taxi horns. It lays U.S. currency in place of eggs.

- Turnip Termites — Looking like a cross between a locust and a piranha, billions of these insatiable pests swarm once a year to their ancient feeding ground, Dogpatch.

- Shminks — Valued for making coats. They can only be captured by hitting them in the head with a kitchen door.

- Pincushions — Alien beings from "Planet Pincus No. 7". Like the earlier Moon Critters, they look like flying sausages with pinwheels on their posteriors.

- Abominable Snow-Hams — Delicious but intelligent and sensitive beings. They present Tiny Yokum with an ethical dilemma, if eating one constitutes cannibalism.

- The Slobbovian Amp-Eater — A luminous beast that consumes electric currents, creating an energy crisis.

- Bashful Bulganiks — Timid birds that are so skittish they can not be seen by human eyes, and are thus theoretical.

- Stunflowers — Murderous anthropomorphic houseplants; anyone trying to pick their seeds falls into the Bottomless Canyon.

- Fatoceroses — Bloated pachyderms against which the only defense is a plate of lethally addictive "Mockaroni".

- Bitingales — Small, fiendish birds whose bite causes unbearable heat for 24 years.

- The Slobbovian King Crab — A huge crustacean that only eats Slobbovian kings. Later supplemented by a marsupial called the Kingaroo which only eats Slobbovian kings.

- The Flapaloo — A scrawny, prehistoric bird that lays 1,000 eggs per minute. The eggs, when dissolved, turn water into gasoline. The oil industry captures the last one in existence and kills it.

- Gobbleglops — Insatiable creatures that look like a cross between a hog and a teddy bear. They eat garbage and cannot be touched, as they are red-hot, living incinerators. Mammy leads them to America's major polluted cities, where they devour all the garbage.[38] When the garbage runs out, they begin to consume everything and everyone in sight.

- Shmeagles — The world's most amorous creatures; the males pursue the females at the speed of light or faster.

- Hammus Alabammus — The Faux Latin designation for an adorable and delicious species of swine, with a "zoot snoot" and a "drape shape". The only known female in existence resides with the Yokums as their beloved pet, Salomey.

Dialogue and catchphrases

Capp, a northeasterner, wrote all the dialogue in Li'l Abner using his approximation of a mock-southern dialect (including phonetic sounds, eye dialect, incorrect spelling, and malapropisms). He interspersed boldface type and included prompt words in parentheses (chuckle!, sob!, gasp!, shudder!, smack!, drool!, cackle!, snort!, gulp!, blush!, ugh!, etc.) to bolster the effect of the speech balloons. Almost every line was followed by two exclamation marks for added emphasis.

Outside Dogpatch, characters use a variety of stock Vaudevillian dialects. Mobsters and criminals speak slangy Brooklynese, and residents of Lower Slobbovia speak pidgin-Russian, some Yinglish. British characters also have comical dialects — like H'Inspector Blugstone of Scotland Yard (who has a Cockney accent) and Sir Cecil Cesspool (whose speech is a clipped King's English). Various Asian, Latin, Native American, and European characters speak in a wide range of caricatured dialects as well. Capp has credited his inspiration for vividly stylized language to early literary influences like Charles Dickens, Mark Twain and Damon Runyon, as well as old-time radio and the burlesque stage.

Comics historian Don Markstein has commented that Capp's "use of language was both unique and universally appealing; and his clean, bold cartooning style provided a perfect vehicle for his creations."[39]

The following is a partial list of characteristic expressions that appear often in Li'l Abner:

- "Natcherly!"

- "Amoozin' but confoozin'!"

- "Yo' big, sloppy beast!!" (also, "Yo' mizzable skonk!!")

- "Ef Ah had mah druthers, Ah'd druther..."

- "As any fool kin plainly see!" (Response: "Ah sees!")

- "What's good for General Bullmoose is good for everybody!" (Variant from the movie: "...good for the USA!")

- "Thar's no Jack S. like our Jack S!"

- "Oh, happy day!"

- "Th' ideel o' ev'ry one hunnerd percent, red-blooded American boy!"

- "Ah'll bash yore haid in!!"

- "Wal, fry mah hide!" (also, "Wal, cuss mah bones!")

- "Ah has spoken!"

- "Good is better than evil becuz it's nicer!"

- "It hain't hoomin, thass whut it hain't!"

Toppers and alternate strips

Li'l Abner had several toppers on the Sunday page, including[4]

- Washable Jones (February 24 – June 9, 1935)

- Advice fo' Chillun, aka Advice fo' Gals, Advice fo' Parents, Advice fo' Yo' All and other titles (June 23, 1935 – Aug 15, 1943)

- Small Change, a.k.a. Small Fry (May 31, 1942 – 1944)

The Sunday page debuted six months into the run of the strip. The first topper was Washable Jones, a weekly continuity about a four-year-old hillbilly boy (Washable Jones) who goes fishing and accidentally hooks a ghost.[40] Capp ended the strip with Washable's mother waking him up, revealing that the story was a dream. After this, Capp expanded Li'l Abner by another row and filled the rest of the space with a page-wide title panel and a small panel called Advice fo' Chillun.[41] Washable Jones appeared in the strip in 1949, and appeared with the Shmoos in two one-shot comics – Al Capp's Shmoo in Washable Jones' Travels (1950, a premium for Oxydol laundry detergent) and Washable Jones and the Shmoo #1 (1953, published by the Capp-owned publisher Toby Press).

Al Capp also wrote two other daily comic strips:[4]

- Abbie an' Slats, drawn by Raeburn Van Buren (Capp wrote the strip from July 12, 1937, through 1945: writing of the strip was continued by Capp's brother Elliot Caplin until the strip's end on January 30, 1971).

- Long Sam, drawn by Bob Lubbers (Capp wrote the strip from May 31, 1954 to sometime in 1955; writing of the strip was continued by Elliot Caplin for a time, and then by Lubbers until the strip ended on December 29, 1962).

Licensing, advertising and promotion

Capp devised several publicity campaigns to boost circulation and increase public visibility of Li'l Abner, often coordinating with national magazines, radio and television. In 1946, Capp persuaded six of the most popular radio personalities (Frank Sinatra, Kate Smith, Danny Kaye, Bob Hope, Fred Waring, and Smilin' Jack Smith) to broadcast a song he'd written for Daisy Mae: (Li'l Abner) Don't Marry That Girl!![42] Other promotional tie-ins included the Lena the Hyena Contest (1946), the Name the Shmoo Contest (1949), the Nancy O. Contest (1951), and the Roger the Lodger Contest (1964).

Li'l Abner characters were often featured in mid-century American advertising campaigns including Grape-Nuts cereal, Kraft caramels, Ivory soap, Oxydol, Duz and Dreft detergents, Fruit of the Loom, Orange Crush, Nestlé cocoa, Cheney neckties, Pedigree pencils, Strunk chainsaws, U.S. Royal tires, Head & Shoulders shampoo, and General Electric light bulbs. There were Dogpatch-themed family restaurants called "Li'l Abner's" in Louisville, Kentucky, Morton Grove, Illinois, and Seattle, Washington.

Capp himself appeared in numerous print ads: Chesterfield cigarettes (he was a lifelong chainsmoker); Schaeffer fountain pen with his friends Milton Caniff and Walt Kelly; the Famous Artists School (in which he had a financial interest) along with Caniff, Rube Goldberg, Virgil Partch, Willard Mullin, and Whitney Darrow Jr.; and, though a teetotaler, Rheingold Beer.

- Cream of Wheat: Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Li'l Abner was the spokesman for Cream of Wheat cereal in a long-running series of comic strip-format ads that appeared in national magazines including Life, Good Housekeeping, and Ladies' Home Journal. The ads usually featured Daisy Mae calling for help against a threat — Earthquake McGoon, a gorilla, a grizzly bear, a rampaging moose, an attack from a Native American, or a natural disaster. Abner is dispatched to rescue her, but not before enjoying an enriched bowl of Cream of Wheat.[43]

- Wildroot Cream-Oil: Fearless Fosdick was licensed for use in an advertising campaign for Wildroot Cream-Oil, a popular men's hair tonic. Fosdick's profile on advertising displays became a prominent fixture in barbershops across America — advising readers to "Get Wildroot Cream-Oil, Charlie!" A series of ads appeared in newspapers, magazines and comic books featuring Fosdick's battles with Anyface, a murderous master of disguise. Anyface was always given away by his dandruff and messy hair.

- Toys and licensed merchandise: Dogpatch characters were heavily licensed throughout the 1940s and 1950s: the main cast was produced as a set of six hand puppets and 14-inch (360 mm) dolls by Baby Barry Toys in 1957. A 10-figure set of carnival chalkware statues of Dogpatch characters was manufactured by Artrix Products in 1951, and Topstone introduced a line of 16 rubber Halloween masks prior to 1960. After the introduction of the Shmoos, they were licensed everywhere in 1948 and 1949. A garment factory in Baltimore made a line of Schmoo apparel — including "Shmooveralls", Shmoo dolls, clocks, watches, jewelry, earmuffs, wallpaper, fishing lures, air fresheners, soap, ice cream, balloons, ashtrays, comic books, records, sheet music, toys, games, Halloween masks, salt and pepper shakers, decals, pinbacks, tumblers, coin banks, greeting cards, planters, neckties, suspenders, belts, curtains, and fountain pens. In one year, Shmoo merchandise generated over $25 million in sales. Close to a hundred licensed Shmoo products from 75 different manufacturers were produced, some of which sold five million units each.[44] Dark Horse Comics issued figures of Abner, Daisy Mae, Fosdick, and the Shmoo in 2000 as part of their line of Classic Comic Characters — statues #8, 9, 17 and 31, respectively.

- Kickapoo Joy Juice: Kickapoo Joy Juice, featured in the strip and as lethal moonshine (it could also remove hair, paint, and tattoos) has been a licensed brand in real life since 1965. The National NuGrape Company first produced the beverage, which was acquired in 1968 by the Moxie Company, and eventually the Monarch Beverage Company of Atlanta, Georgia. The actual product is a soft drink. The label features Hairless Joe and Lonesome Polecat. Distribution currently includes the United States, Canada, Singapore, Bangladesh, China, Pakistan, Malaysia, Mongolia, Brunei, Indonesia, and Thailand.[45]

- Dogpatch USA: In 1968, an 800-acre (3.2 km2), $35 million theme park called Dogpatch USA opened in Marble Falls, Arkansas, based on Capp's work and with his support. The gift shops sold souvenirs like corncob pipes and moonshine jugs. In addition to the newly constructed rides and attractions, many of the buildings in the park were authentic 19th-century log structures purchased by general manager James H. Schermerhorn. The logs in each building were numbered, cataloged, disassembled and reassembled at the park. Dogpatch USA was a popular attraction during the 1970s, but was closed in 1993 due to mismanagement and financial difficulties. Several attempts have been made to reopen the park but it remains abandoned. As of late 2005, the area has been stripped by vandals and souvenir hunters, and is today slowly being reclaimed by the surrounding Arkansas wilderness. There were plans for it to reopen in 2018, but they fell through.[46]

Awards and recognition

Li'l Abner was a comic strip with fire in its belly and a brain in its head.

— John Updike, from My Well-Balanced Life on a Wooden Leg (1991)

Fans of the strip include novelist John Steinbeck, who called Capp "very possibly the best writer in the world today" in 1953 and recommended him for the Nobel Prize in literature, and media critic and theorist Marshall McLuhan, who considered Capp "the only robust satirical force in American life." John Updike, calling Li'l Abner a "hillbilly Candide", said that the strip's "richness of social and philosophical commentary approached the Voltairean."[47] Capp has been compared to Fyodor Dostoevsky, Jonathan Swift, Laurence Sterne, and François Rabelais.[48] Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly and Time called him "the Mark Twain of cartoonists". Charlie Chaplin, William F. Buckley, Al Hirschfeld, Harpo Marx, Russ Meyer, John Kenneth Galbraith, Ralph Bakshi, Shel Silverstein, Hugh Downs, Gene Shalit, Frank Cho, Daniel Clowes,[49] and Queen Elizabeth are all reportedly fans of Li'l Abner.

In book Understanding Media, Marshall McLuhan called Li'l Abner's Dogpatch "a paradigm of the human situation". Comparing Capp to other contemporary humorists, McLuhan wrote: "Arno, Nash, and Thurber are brittle, wistful little précieux beside Capp!" In his essay "The Decline of the Comics", (Canadian Forum, January 1954) literary critic Hugh MacLean classified American comic strips into four types: daily gag, adventure, soap opera, and "an almost lost comic ideal: the disinterested comment on life's pattern and meaning." In the fourth type, according to MacLean, there were only two: Pogo and Li'l Abner. In 2002, the Chicago Tribune, in a review of The Short Life and Happy Times of the Shmoo, noted: "The wry, ornery, brilliantly perceptive satirist will go down as one of the Great American Humorists." In America's Great Comic Strip Artists (1997), comics historian Richard Marschall analyzed the misanthropic subtext of Li'l Abner:

Capp was calling society absurd, not just silly; human nature not simply misguided, but irredeemably and irreducibly corrupt. Unlike any other strip, and indeed unlike many other pieces of literature, Li'l Abner was more than a satire of the human condition. It was a commentary on human nature itself.

Li'l Abner was also the subject of the first book-length, scholarly assessment of a comic strip ever published; Li'l Abner: A Study in American Satire by Arthur Asa Berger (Twayne, 1969) contained serious analyses of Capp's narrative technique, use of dialogue, self-caricature and grotesquerie, the strip's overall place in American satire, and the significance of social criticism and the graphic image. "One of the few strips ever taken seriously by students of American culture," wrote Berger, "Li'l Abner is worth studying...because of Capp's imagination and artistry, and because of the strip's very obvious social relevance." The book was reprinted by the University Press of Mississippi in 1994.

Al Capp's life and career are the subjects of a life-sized mural commemorating his 100th birthday, displayed in downtown Amesbury, Massachusetts.[50][51] According to The Boston Globe, the town renamed its amphitheatre in his honor.

- National Cartoonists Society[52] Reuben Award (1947) for "Cartoonist of the Year".

- Inkpot Award (1978) from Comic-Con International.

- National Cartoonists Society Elzie Segar Award (1979) for a "unique and outstanding contribution to the profession of cartooning."

- Inductee into the National Cartoon Museum (formerly the International Museum of Cartoon Art) Hall of Fame (one of only 31 artists).

- Inductee into the Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame in 2004.

- Li'l Abner was one of 20 American comic strips included in the Comic Strip Classics series of United States Postal Service commemorative stamps.[39]

Influence and legacy

Sadie Hawkins Day

Sadie Hawkins Day is a pseudo-holiday created in the strip. It first appeared in Li'l Abner on November 15, 1937. Capp originally created it as a comedic plot device, but in 1939, two years after its debut, a double-page spread in Life proclaimed, "On Sadie Hawkins Day Girls Chase Boys in 201 Colleges". By 1952, the event was reportedly celebrated at 40,000 venues. It became a rite of women's empowerment at high schools and college campuses before second-wave feminism gained prominence.

Outside of the comic strip, a Sadie Hawkins dance is a gender role reversal. Women and girls take the initiative in inviting a man or boy out on a date — almost unheard of before 1937 — to a dance. When Capp created the event, it wasn't his intention to have it occur annually on a specific date. However, due to its enormous popularity and the numerous fan letters he received, Capp made it a tradition in the strip every November, lasting four decades. In many localities, the tradition still continues.

Al Capp ended his comic strip by setting a date for Sadie Hawkins Day. In the strip on November 5, 1977, Li'l Abner and Daisy Mae make a final visit to Capp, and Daisy insists that Capp settle on a date. Capp suggests November 26, and Daisy rewarded him with a kiss.[53]

Language

Sadie Hawkins Day and Sadie Hawkins dance are two of several terms attributed to Capp that have entered the English lexicon. Others include double whammy, skunkworks, and Lower Slobbovia. The term shmoo is used in defining technical concepts in four fields of science.[54]

- In socioeconomics, a "shmoo" refers to any generic kind of good that reproduces itself (as opposed to widgets which require resources and active production).

- In microbiology, "shmooing" is the biological term used for the budding process in yeast reproduction. The cellular bulge produced by a haploid yeast cell towards a cell of the opposite mating type during the mating of yeast is referred to as a "shmoo", due to its structural resemblance to the cartoon character.

- In particle physics, a "shmoo" refers to a high-energy survey instrument – as utilized at the Los Alamos National Laboratory for the Cygnus X-3 Sky Survey performed at the LAMPF (Los Alamos Meson Physics Facility) grounds. Over one hundred white "shmoo" detectors were sprinkled around the accelerator beamstop area and adjacent mesa to capture Subatomic cosmic ray particles emitted from the constellation Cygnus. The detectors housed scintillators and photomultipliers in an array that gave the detector its Shmoo-like shape.

- In electrical engineering, a shmoo plot is the technical term used for the graphic pattern of test circuits. (The term is also used as a verb: to "shmoo" means to run the test.)

Capp has been credited with popularizing terms such as "natcherly", schmooze, druthers, nogoodnik, and neatnik. (In his book The American Language, H. L. Mencken credits the postwar trend of adding "-nik" to the ends of adjectives to create nouns as beginning in Li'l Abner.)

Franchise ownership and creators' rights

In the late 1940s, newspaper syndicates typically owned the copyrights, trademarks, and licensing rights to comic strips. According to publisher Denis Kitchen, "Nearly all comic strips, even today, are owned and controlled by syndicates, not the strips' creators. And virtually all cartoonists remain content with their diluted share of any merchandising revenue their syndicates arrange. When the starving and broke Capp first sold Li'l Abner in 1934, he gladly accepted the syndicate's standard onerous contract. But in 1947 Capp sued United Feature Syndicate for $14 million, publicly embarrassed UFS in Li'l Abner, and wrested ownership and control of his creation the following year."[55]

In an October 1947 strip, Li'l Abner met Rockwell P. Squeezeblood, head of the corrupt Squeezeblood Syndicate, a thinly veiled dig at the United Feature Syndicate. The resulting sequence, "Jack Jawbreaker Fights Crime!!", was a satire of DC Comics's notorious exploitation of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster over Superman. It was later reprinted in The World of Li'l Abner (1953).

In 1964, Capp left United Features and took Li'l Abner to the Chicago Tribune New York News Syndicate.[56]

Integration of women in the NCS

Capp was outspoken in favor of diversifying the National Cartoonists Society by admitting women cartoonists. The NCS had originally disallowed female members into its ranks. In 1949, when they refused membership to Hilda Terry, creator of the comic strip Teena, Capp temporarily resigned in protest. "Capp had always advocated a more activist agenda for the Society, and he had begun in December 1949 to make his case in the Newsletter as well as at the meetings," wrote comics historian R. C. Harvey.[57] According to Tom Roberts, author of Alex Raymond: His Life and Art (2007), Capp authored a monologue that was instrumental in changing the rules the following year. Hilda Terry was the first woman cartoonist admitted in 1950.

Social commentary in comic strips

Through Li'l Abner, the American comic strip achieved unprecedented relevance in the postwar years, attracting new readers who were more intellectual and informed on current events (according to Coulton Waugh, author of The Comics, 1947). "When Li'l Abner made its debut in 1934, the vast majority of comic strips were designed chiefly to amuse or thrill their readers. Capp turned that world upside-down by routinely injecting politics and social commentary into Li'l Abner," wrote comics historian Rick Marschall in America's Great Comic Strip Artists (1989). With adult readers far outnumbering young ones, Li'l Abner cleared away the concept that humor strips were solely the domain of adolescents and children. Li'l Abner provided a new template for contemporary satire and personal expression in comics, paving the way for Pogo, Feiffer, Doonesbury, and MAD.

Mad

Fearless Fosdick and other Li'l Abner comic strip parodies, such as "Jack Jawbreaker!" (1947) and "Little Fanny Gooney" (1952), were likely an inspiration to Harvey Kurtzman when he created Mad, which began in 1952 as a comic book that parodied other comics in the same manner. By the time EC Comics published Mad #1, Capp had been doing Fearless Fosdick for nearly a decade. Similarities between Li'l Abner and the early Mad include the incongruous use of mock-Yiddish slang terms, the disdain for pop culture icons, the black humor, the dearth of sentiment, and the broad visual styling. The trademark comic signs that clutter the backgrounds of Will Elder's panels had a precedent in Li'l Abner, in the residence of Dogpatch entrepreneur Available Jones, though they're also reminiscent of Bill Holman's Smokey Stover. Kurtzman resisted doing feature parodies of either Li'l Abner or Dick Tracy in Mad, despite their prominence.

Capp is one of the great unsung heroes of comics. I've never heard anyone mention this, but Capp is 100% responsible for inspiring Harvey Kurtzman to create Mad Magazine. Just look at Fearless Fosdick — a brilliant parody of Dick Tracy with all those bullet holes and stuff. Then look at Mad's "Teddy and the Pirates", "Superduperman!" or even Little Annie Fanny. Forget about it — slam dunk! Not taking anything away from Kurtzman, who was brilliant himself, but Capp was the source for that whole sense of satire in comics. Kurtzman carried that forward and passed it down to a whole new crop of cartoonists, myself included. Capp was a genius. You wanna argue about it? I'll fight ya, and I'll win!

— Ralph Bakshi at ASIFA-Hollywood, April 2008

Parodies and imitations

Al Capp once told one of his assistants that he knew Li'l Abner had finally "arrived" when it was first pirated as a pornographic Tijuana bible parody in the mid-1930s.[58] Li'l Abner was also parodied in 1954 (as "Li'l Melvin" by "Ol' Hatt") in the pages of EC Comics' humor comic, Panic, edited by Al Feldstein.[59] Kurtzman eventually did spoof Li'l Abner (as "Li'l Ab'r") in 1957, in his short-lived humor magazine, Trump. Both the Trump and Panic parodies were drawn by Will Elder. In 1947, Will Eisner's The Spirit satirized the comic strip business in general, as a denizen of Central City tries to murder cartoonist "Al Slapp", creator of "Li'l Adam". Capp was also caricatured as an ill-mannered, boozy cartoonist (Capp was a teetotaler in real life) named "Hal Rapp" in the comic strip Mary Worth by Allen Saunders and Ken Ernst. Supposedly done in retaliation for Capp's "Mary Worm" parody in Li'l Abner (1956), a media-fed "feud" commenced briefly between the rival strips. It turned out to be a collaborative hoax by Capp and his longtime friend Saunders as a publicity stunt.

Li'l Abner's success also sparked some comic strip imitators. Jasper Jooks by Jess "Baldy" Benton (1948–'49), Ozark Ike (1945–'53), and Cotton Woods (1955–'58), both by Ray Gotto, were inspired by Capp's strip. Boody Rogers' Babe was a series of comic books about a beautiful hillbilly girl who lives with her kin in the Ozarks, with many similarities to Li'l Abner. Looie Lazybones, an overt imitation (drawn by Frank Frazetta) ran in several issues of Standard's Thrilling Comics in the late 1940s. Charlton Comics published the short-lived Hillbilly Comics by Art Gates in 1955, featuring "Gumbo Galahad", who looked identical to Li'l Abner, similar to Pokey Oakey by Don Dean, which ran in MLJ's Top-Notch Laugh and Pep Comics. Later, many fans and critics saw Paul Henning's popular TV sitcom, The Beverly Hillbillies (1962–'71) as inspired by Li'l Abner, prompting Alvin Toffler to ask Capp about the similarities in a 1965 Playboy interview.

Popularity and production

Li'l Abner made its debut on August 13, 1934, in eight North American newspapers, including the New-York Mirror. Initially owned and syndicated through United Feature Syndicate, a division of the E. W. Scripps Company, it was an immediate success. According to publisher Denis Kitchen, Capp's "hapless Dogpatchers hit a nerve in Depression-era America. Within three years Abner's circulation climbed to 253 newspapers, reaching over 15,000,000 readers. Before long he was in hundreds more, with a total readership exceeding 60,000,000."[55] At its peak, the strip was read daily by 70 million Americans with a circulation of more than 900 newspapers in North America and Europe.

During the peak of the strip, Capp's workload grew to include advertising, merchandising, promotional work, comic book adaptations, and public service material in addition to the regular six dailies and one Sunday strip per week. Capp had a team of assistants in later years who worked under his direct supervision. They included Andy Amato, Harvey Curtis, Walter Johnson, and Frank Frazetta, who penciled the Sunday continuity from studio roughs from 1954 to the end of 1961 before his fame as a fantasy artist.

Due to his own experience working on Joe Palooka, Capp frequently drew attention to his assistants in interviews and publicity pieces. A 1950 cover story in Time included photos of two of his employees, whose roles in the production were detailed by Capp. This irregular policy has led to the misconception that his strip was ghostwritten by others. However, the production of Li'l Abner has been well documented, and Capp maintained creative control over every stage of production for virtually the entire run of the strip. Capp originated the stories, wrote the dialogue, designed the major characters, rough penciled the preliminary staging and action of each panel, oversaw the finished pencils, and drew and inked the faces and hands of the characters. "He had the touch," Frazetta said of Capp in 2008. "He knew how to take an otherwise ordinary drawing and really make it pop. I'll never knock his talent."[60]

Many have commented on the shift in Capp's political viewpoint, from as liberal as Pogo in his early years to as conservative as Little Orphan Annie when he reached middle age. At one extreme, he displayed consistently devastating humor, while at the other, his mean-spiritedness came to the fore — but which was which seems to depend on the commentator's own point of view. From beginning to end, Capp was acid-tongued toward the targets of his wit, intolerant of hypocrisy, and always wickedly funny. After about 40 years, however, Capp's interest in Abner waned, and this showed in the strip itself...

— Don Markstein's Toonopedia

Li'l Abner ran until November 13, 1977, when Capp retired with an apology to his fans for the declining quality of the strip, which he said had been the best he could manage due to advancing illness. "If you have any sense of humor about your strip — and I had a sense of humor about mine — you knew that for three- or four-years Abner was wrong. Oh hell, it's like a fighter retiring. I stayed on longer than I should have," he admitted."[61] When the strip retired, People magazine ran a substantial feature and The New York Times devoted nearly a full page to the event, according to publisher Denis Kitchen. Capp, a lifelong chain smoker, died from emphysema two years later at age 70, at his home in South Hampton, New Hampshire, on November 5, 1979.

In 1988 and 1989, many newspapers ran old of Li'l Abner strips, mostly from the 1940s run, distributed by Newspaper Enterprise Association and Capp Enterprises. Following the 1989 revival of Pogo, a revival of Li'l Abner was also planned in 1990. Drawn by cartoonist Steve Stiles,[62] the new Li'l Abner was approved by Capp's widow and his brother Elliott Caplin, but Al Capp's daughter, Julie Capp, objected at the last minute and permission was withdrawn.

Li'l Abner in other media

Radio and recordings

With John Hodiak in the title role, the Li'l Abner radio drama ran weekdays on NBC from Chicago, from November 20, 1939, to December 6, 1940. The rest of the cast included Laurette Fillbrandt as Daisy Mae, Hazel Dopheide as Mammy Yokum, and Clarence Hartzell as Pappy. Durward Kirby was the announcer. The radio show was written by Charles Gussman, who consulted closely with Capp on the storylines.

- The Shmoo Sings with Earl Rogers — 78 rpm (1948) Allegro

- The Shmoo Club b/w The Shmoo Is Clean, the Shmoo Is Neat — 45 rpm (1949) Music You Enjoy, Inc.

- The Snuggable, Huggable Shmoo b/w The Shmoo Doesn't Cost a Cent — 45 rpm (1949) Music You Enjoy, Inc.

- Shmoo Lesson b/w A Shmoo Can Do Most Anything — 45 rpm (1949) Music You Enjoy, Inc.

- Li'l Abner Goes to Town — 78 rpm (1950) Capp-Tone Comic Record

- Li'l Abner (Original Cast Recording) — LP (1956) Columbia Records

- Li'l Abner (Motion Picture Soundtrack) — LP (1959) Columbia Records

- An Interview with Al Capp — EP (1959) Smithsonian Folkways

- Li'l Abner fo' Chillun — LP (c. 1960) 20th Century Studios

- Al Capp on Campus — LP (1969) Jubilee Records

Selections from the Li'l Abner musical have been recorded by Percy Faith, Mario Lanza, André Previn, and Shelly Manne. Over the years, Li'l Abner characters have inspired compositions in pop, jazz, country, and rock and roll:

- The Kickapoo Joy Juice Jolt (1946) from The Li'l Abner Suite, was composed for The Alvino Rey Orchestra by Bud Estes.

- Kickapoo Joy Juice, composed by Duke Ellington, was recorded live at Carnegie Hall in December, 1947.

- Lonesome Polecat, written by Johnny Mercer & Gene de Paul for the musical Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954), was later recorded by Bobby Darin and The McGuire Sisters.

- Fearless Fosdick, composed by Bill Holman, was recorded live in 1954 by Vic Lewis and his Orchestra, featuring Tubby Hayes.

- Daisy Mae, written and recorded by Ernest Tubb, appeared on the Decca Records album The Daddy of 'Em All (1957).

- Kickapoo Joy Juice (1962) written by Jack Greenback, Mel Larson, and Jerry Marcellino, was recorded by The Rivingtons.

- Sadie Hawkins Dance (2001) written by Matt Thiessen, was recorded by Relient K.

- Fearless Fosdick's Tune, composed and recorded by Umberto Fiorentino, appeared on the Brave Art/Columbia-Sony CD Things to Come (2002).

Sheet music

- Li'l Abner — by Ben Oakland, Milton Berle & Milton Drake (1940) Leo Feist Publishers

- Sadie Hawkins Day — by Don Raye & Hughie Prince (1940) Leeds Music

- The USA by Day and the RAF by Night — by Hal Block & Bob Musel (1944) Paramount Music

- (Li'l Abner) Don't Marry That Girl!! — by Al Capp & Sam H. Stept (1946) Barton Music

- The Shmoo Song — by John Jacob Loeb & Jule Styne (1948) Harvey Music

- Shmoo Songs — by Gerald Marks (1949) Bristol Music

- The Kigmy Song — by Joe Rosenfield & Fay Tishman (1949) Town and Country Music Co.

- I'm Lonesome and Disgusted!!! — by "Irving Vermyn" (1956) General Music Publishing Co.

- Namely You — by Johnny Mercer & Gene de Paul (1956) Commander Publications

- Love in a Home — by Johnny Mercer & Gene de Paul (1956) Commander Publications

- If I Had My Druthers — by Johnny Mercer & Gene de Paul (1956) Commander Publications

- Jubilation T. Cornpone — by Johnny Mercer & Gene de Paul (1956) Commander Publications

Comic books and reprints

- Tip Top Comics (1936–1948) anthology (United Feature Syndicate)

- Comics on Parade (1945–1946) anthology (UFS)

- Sparkler Comics (1946–1948) anthology (UFS)

- Li'l Abner (1947) 9 issues (Harvey Comics)

- Li'l Abner (1948) 3 issues (Super Publishing)

- Tip Topper Comics (1949–1954) anthology (UFS)

- Al Capp's Li'l Abner (1949–1955) 28 issues (Toby)[63]

- Al Capp's Shmoo Comics (1949–1950) 5 issues (Toby)

- Al Capp's Dogpatch (1949) 4 issues (Toby)

- Al Capp's Li'l Abner in The Mystery o' the Cave (1950) (Oxydol premium)

- Al Capp's Daisy Mae in Ham Sangwidges (1950) (Oxydol premium)

- Al Capp's Shmoo in Washable Jones' Travels (1950) (Oxydol premium)

- Al Capp's Wolf Gal (1951–1952) 2 issues (Toby)

- Washable Jones and the Shmoo (1953) (Toby)

- Party Time with Coke (1958) monthly digest featuring Al Capp's Boys 'n' Gals (Coca-Cola premium)

Kitchen Sink Press began publishing the Li'l Abner Dailies in hardcover and paperback, one year per volume, in 1988. The demise of KSP in 1999 stopped the reprint series at Volume 27 (1961). Dark Horse Comics reprinted the limited series Al Capp's Li'l Abner: The Frazetta Years, in four full-color volumes covering the Sunday pages from 1954 to 1961. They also released an archive hardcover reprint of the complete Shmoo Comics in 2009, followed by a second Shmoo volume of complete newspaper strips in 2011.

At San Diego Comic-Con in July 2009, IDW Publishing and The Library of American Comics announced the publication of Al Capp's Li'l Abner: The Complete Dailies and Color Sundays: Vol. 1 (1934–1936). The comprehensive series titled Li'l Abner: The Complete Dailies & Color Sundays, a reprinting of the complete 43-year history of Li'l Abner[64] spanning a projected 20 volumes, began on April 7, 2010.

Public service works

Capp provided specialty artwork for civic groups, government agencies, and nonprofit organizations.[65] The following titles are all single-issue, educational comic books and pamphlets produced for public services:

- Al Capp by Li'l Abner — public service giveaway issued by the Red Cross (1946)

- Yo' Bets Yo' Life! — public service giveaway issued by the United States Army (circa 1950)

- Li'l Abner Joins the Navy — public service giveaway issued by the United States Navy (1950)

- Fearless Fosdick and the Case of the Red Feather — public service giveaway issued by Red Feather Services, a forerunner of United Way (1951)

- The Youth You Supervise — public service giveaway issued by the United States Department of Labor (1956)