Paraskeva Friday

In this article, we will explore in depth the topic of Paraskeva Friday, which has been the subject of interest and debate in various areas. From its origins to its relevance today, we will address its many facets and its impact on society. Through an exhaustive and rigorous analysis, we seek to shed light on different aspects related to Paraskeva Friday, providing valuable information and diverse perspectives to enrich the knowledge of our readers. By exposing data, testimonies and relevant studies, we aim to offer a complete and objective vision that allows us to understand the importance of Paraskeva Friday in different contexts and situations.

| Paraskeva Friday | |

|---|---|

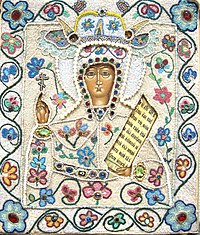

Saint Paraskeva-Friday, Galich, Russia, photo before 1917 | |

| Venerated in | Folk Orthodoxy |

| Equivalents | |

| Indo-European | Priyah |

| Norse | Freyja |

| Slavic | Mokosh[1] |

In the folk Christianity of Slavic Eastern Orthodox Christians, Paraskeva Friday is a mythologized image based on a personification of Friday as the day of the week and the cult of saints Paraskeva of Iconium, called Friday and Paraskeva of the Balkans.[1] In folk tradition, the image of Paraskeva Friday correlates with the image of Saint Anastasia of the Lady of Sorrows, and the Saint Nedelya as a personified image of Sunday.[1] Typologically, Paraskeva Pyatnitsa has parallels with day-personifications of other cultures, for example, the Tajik Bibi-Seshanbi ('Lady Tuesday').[2]: 368

Etymology

The word paraskeva (Greek: παρασκευη, Greek pronunciation: [/pa.ɾa.sceˈvi/]) means "preparation ".[citation needed]

Image

The image of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa according to folk beliefs is different from the iconographic image, where she is depicted as an ascetic-looking woman in a red maforiya. The carved icon of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa from the village of Illyeshi is widely known. It is revered in the Russian Orthodox Church as a miracle worker and is housed in the Trinity Cathedral of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra in St. Petersburg.[3]

The most common idol was the sculpture of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa – not only for Russians, but also for neighbouring peoples.[4] The folklorist A. F. Mozharovsky writing in 1903,[a] noted that in the chapels "in foreign areas" there were "roughly carved wooden images of Saints Paraskeva and Nicholas ... All carved images of Saints Paraskeva and Nicholas have the common name of Pyatnits ".[5] Sculptures were widespread among the Russians. According to a 1908 historical sketch of Sevsk, Dmitrovsk and Komaritskaya volost by Svyatsky, commonly, Paraskeva were:[6]: 22 "a painted wooden statue of Pyatnitsa, sometimes in the form of a woman in oriental attire, and sometimes in the form of a simple woman in poneva and lapti ... placed in churches in special cabinets and people prayed before this image".

The popular imagination sometimes gave Paraskeva Friday demonic features: tall stature, long loose hair, large breasts, which she throws behind her back, which brings her closer to the female mythological characters like Dola, Death, and Rusalka (mermaid).

Depictions and traditions

For East Slavs, Paraskeva Friday is a personified representation of the day of the week.[7] She was called Linyanitsa, Paraskeva Pyatnitsa, Paraskeva Lyanyanikha, Nenila Linyanitsa. Paraskeva Friday was dedicated 27 [O.S. ] October as Paraskeva Muddyha Day and [O.S. ] 10 November as Day of Paraskeva the Flaxwoman. In the church, these days commemorate Paraskeva of the Balkans and Paraskeva of Iconium, respectively. On these days, no spinning, washing, or ploughing was done so as not to "dust the Paraskeva or to clog her eyes."[citation needed] It was believed that if the ban was violated, she could inflict disease. One of the decrees of the Stoglav Synod (1551) is devoted to the condemnation of such superstitions:[4]

Yes, by pogosts and by the villages walk false prophets, men and wives, and maidens, and old women, naked and barefoot, and with their hair straight and loose, shaking and being killed. And they say that they are Saint Friday and Saint Anastasia and that they command them to command the canons of the church. They also command the peasants in Wednesday and in Friday not to do manual labour, and to wives not to spin, and not to wash clothes, and not to kindle stones.

According to beliefs, Paraskeva Friday also oversees the observance of other Friday prohibitions, including washing laundry, bleaching canvases, and combing hair.[8]: 445 In the stories Paraskeva Pyatnitsa spins the kudel left by the mistress,[1] punishes the woman who violated the ban, tangles the thread, maybe skin the offending woman, takes away her eyesight, turns her into a frog, or throws forty spindles into the window with orders to strain them until morning.[9]

There was a ritual of "driving Pyatnitsa" documented in the 18th century: "In Small Russia, in the Starodubsky regiment on a holiday day they drive a plain-haired woman named Pyatnitsa, and they drive her in the church and at church people honour her with gifts and with the hope of some benefit".[9][10]: 168 Until the 19th century, the custom of "leading (driving) Pyatnitsa" – a woman with loose hair – was preserved in Ukraine.[11]

Among Ukrainians there was a belief that Friday walks were littered with needles and spindles of negligent hosts who did not honour the saint and her days. [11]

In bylichki and spiritual verses, Paraskeva Pyatnitsa complains that she is not honoured by not observing the Friday prohibitions – they prick her with spindles, spin her hair, clog her eyes with kostra (shives). The icons depict Paraskeva Friday with spokes or spindles sticking out of her chest (compare with images of Our Lady of the Seven Spears or Softening of the Evil Hearts).[1]

In eastern Slavic cultures, wooden sculptures of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa were also placed on wells, sacrifices were brought to her. The sacrifices, emblematic of women's work, might be clothes, kudel (long bundle of fibre for spinning), threads, and sheep's wool; these were thrown down a well. The rite was called mokrida, which may allude to Mokosh.[12]

The Russians prayed to Paraskeva Pyatnitsa for protection against the death of livestock, especially cows. The saint was also considered the healer of human ailments, especially devil's obsession, fever, toothache, headache, and other ailments.[citation needed]

Ninth Friday

The celebration of the ninth Friday after Easter was widespread among Russians. In Solikamsk, the miraculous deliverance of the city from the invasion of Nogais and Voguls in 1547 was remembered on this day.[13]

In Nikolsky County, Vologda province, on the ninth Friday there was a custom to "build a customary linen": the girls would come together, rub the flax, spin and weave the linen in a day.[4]

For the Komi peoples, the ninth Friday was called the "Covenant Day of the Sick" (Komi: Zavetnoy lun vysysyaslӧn). It was believed that on this day the miracle-working icon of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa (Komi: Paraskeva-Peknicha) from the chapel in the village of Krivoy Navolok could bring healing to the sick. There is still a tradition of crucession to the Ker-yu river, where elderly women and girls wash temple and home icons in the waters blessed with the icon of Paraskeva Pyatnitsa. The water is considered holy for three days after the feast and is collected and taken away with them. Dipping icons in standing water was considered a sin.[14]

In folk calendars

Among the South Slavs, the day of [O.S. October] 27 is celebrated everywhere.

In some regions of Serbia and Bosnia, they also celebrate 8 August [O.S. ], called in Serbian: Petka Trnovska, Petka Trnovka, and in Macedonian: Trnovka Petka, Mlada Petka, Petka Vodonosha. In Bulgarian Thrace, St. Petka is dedicated to the Friday after Easter, and in Serbia, the Friday (Požega) before St. Evdokija Day (14 [O.S. ] March).[1]

In Bulgarian it is known as Petkovden, St. Petka, Petka, or Pejcinden. In Macedonian: Petkovden; and in Serbian: Petkovica, Petkovaca, Sveta Paraskeva, Sveta Petka, Pejcindan.

See also

Notes

- ^ According to Mozharovsky:[5]

... на придорожныя часовенки-пятницы ставятся иконы св. Параскевы. Теперь это такъ, но было время, что въ часовенки въ инородческихъ мѣст-ностяхъ ставились рѣзныя изображенія изъ дерева грубой работы св. Параскевы и Николая угодника. Они были одѣты въ соотвѣтственныя облаченія. Николай Чудотворецъ въ свя тительскія ризы, а великомученица Параскева была одѣта въ тз'ник\' христіанки первыхъ вѣковъ изъ бѣлаго холста и закрашена разными самотканными убрз'сами, поясами и т. п. Къ часовнямъ приходили мѣстные инородцы: чз'ваши, черемисы, мордва, вотяки, мещеры и даже рзт сскіе. Они з'сердно молились иконамъ рѣзнымъ, ставили свѣчи, жертвовали деньги, клали яйца и вѣшали полотенца. Такія рѣзныя изображенія святой Параскевы и Николая Чудотворца еще и нынѣ можно видѣть въ каменныхъ часовняхъ на торговыхъ плоиіадяхъ въ г.г. Козмодемьянскѣ, Чебоксарахъ, въ селѣ Остолоповѣ, Казанской губ., и другихъ. чѣстахъ. Всѣ рѣзныя изображенія святыхъ Параскевы и Николая носятъ общее названіе пятницъ.

... cons of St. Paraskeva are placed on roadside chapels on Fridays. This is true now, but there was a time when roughly carved wooden images of St. Paraskeva and St. Nicholas were placed in chapels in foreign areas. They were dressed in appropriate vestments. Nicholas the Wonderworker in priestly vestments, and the Great Martyr Paraskeva was dressed in the Christian attire of the first centuries made of white linen and covered with various homespun ornaments, belts, etc. Local foreigners came to the chapels: the Chzvashi, Cheremis, Mordvins, Votyaks, Meshchers, and even Russians. They prayed fervently to the carved icons, lit candles, donated money, laid eggs, and hung towels. Such carved images of Saint Paraskeva and Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker can still be seen today in stone chapels on trading squares in the cities of Kozmodemyansk, Cheboksary, in the village of Ostolopovo, Kazan province, and other places. All carved images of Saints Paraskeva and Nicholas bear the common name of Fridays.

—Mozharovsky (1902). pp. 25–26 —English translation

References

- ^ a b c d e f Levkievskaya, Elena Evgenievna; Tolstaya, Svetlana Mikhailovna (2004). "Paraskeva Pyatnitsa" Параскева Пятница. In N. I. Tolstoy; S. M Tolstaya; SDES Editorial Board Institute for Slavic Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (eds.). Slavi︠a︡nskie drevnosti: ėtnolingvisticheskiĭ slovarʹ (SDES) Славянские древности: Этнолингвистический словарь (СДЭС) [Slavic Antiquities: Ethnolinguistic Dictionary]. Vol. 3: К (Круг) — П (Перепелка). Moskva: Mezhdunarodnye otnoshenii︠a︡. pp. 631–633. ISBN 978-5-7133-1312-8. ISBN 5-7133-1207-0

- ^ Buranok, O. M., ed. (1996). Problemy sovremennogo izuchenii︠a︡ russkogo i zarubezhnogo istoriko-literaturnogo prot︠s︡essa Проблемы современного изучения русского и зарубежного историко-литературного процесса [Problems of modern study of Russian and foreign historical and literary process] (in Russian). Samara: Izd-vo SamGPU. ISBN 9785842800841. Materialy XXV Zonaln̆oĭ nauchno-prakticheskoĭ konferent︠s︡ii literaturovedov Povolzhʹi︠a︡ i Bochkarevskikh chteniĭ, 22-25 mai︠a︡ 1996 goda. .

- ^ Startseva, Yulia Vladimirovna; Popov, I. V. (2001). Явление вмц. Параскевы Пятницы в Ильешах [Appearance of the Great Martyr Paraskeva Pyatnitsa in Ilyeshi] (PDF). Санкт-Петербургские Епархиальные ведомости (in Russian). No. 25. pp. 91–96. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2024.

- ^ a b c Chicherov, Vladimir Ivanovich (1957). Зимний период русского народного земледельческого календаря XVI – XIX веков [Winter period of the Russian folk agricultural calendar of the 16th – 19th centuries] (in Russian). Мoscow: Издательство Академии Наук СССР. p. 237.

- ^ a b Mozharovsky, Alexander Fedorovich (1903). Отголоски старины и народности собрание очерков и заметок из периодических изданий [Echoes of antiquity and nationality: A collection of essays and notes from periodicals] (in Russian). Tambov, Russia: N. I. Berdonosov and F. Ya. Prigorin. pp. 25–26. Archived from the original on 9 November 2024.

- ^ Svyatsky, D. O. (1908). Исторический очерк городов Севска, Дмитровска и Комарицкой волости [Historical sketch of the cities of Sevsk, Dmitrovsk and Komaritskaya volost] (in Russian). (Author: Святский Д. О.).

- ^ Kruk, I. I.; Kotovich, Oksana (2003). Koleso vremeni: tradit︠s︡ii i sovremennostʹ Колесо времени: традиции и современность [Wheel of Time: Traditions and Modernity] (in Russian). Minsk, Belarus: Беларусь издательство. p. 44. ISBN 985-01-0477-5.

- ^ Shchepanskaya, T. B. (2003). Культура дороги в русской мифоритуальной традиции XIX – XX вв [The Culture of the Road in the Russian Mythological and Ritual Tradition of the 19th – 20th Centuries]. Современные исследования, Традиционная духовная культура славян . Мoscow: Indrik. p. 528. ISBN 5-85759-176-7. (Author: Щепанская Т. Б.; surname also rendered Szczepanska). Publisher' notes Archived 2016-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Madlevskaya, E.; Eriashvili, N.; Pavlovsky, V. (2007). "Russkaâ mifologiâ: ènciklopediâ" Параскева Пятница [Paraskeva Pyatnitsa]. Russkaya mifologiya. Moscow: Èksmo. pp. 692–706. ISBN 978-5-699-13535-6.

- ^ Lavrov, A. S. (2000). Koldovstvo i religii︠a︡ v Rossii: 1700–1740 gg Колдовство и религия в России: 1700—1740 гг [Witchcraft and Religion in Russia: 1700–1740] (in Russian). Moskva: Drevlekhranilishche. ISBN 5-93646-006-1.

- ^ a b Voropay, Alexey Ivanovich (1958). Звичаї нашого народу [Customs of our people] (PDF) (in Ukrainian). Vol. 2. Munich: Українське видавництво. p. 165.

- ^ Kalinsky, I. (2008). T︠S︡erkovno-narodnyĭ mesi︠a︡t︠s︡eslov na Rusi Церковно-народный месяцеслов на Руси [Church and folk calendar in Rus'] (in Russian). Moskva: ĖKSMO. ISBN 978-5-699-27691-2.

- ^ "The Ninth Friday after Easter in Solikamsk". Archived from the original on 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

- ^ Sharapov, Valery Е. (2003). "Paraskeva-Pekriica ew. – St. Paraskeva martyr, named P'yatnitsa (Russ. pyatnitsa 'Friday')". In Vladimir Napolskikh; Anna-Leena Siikala; Hoppál Mihály (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Uralic Mythologies. Vol. I. Komi Mythology. Translated by Sergei Belykh. Translation revised by Peter Meikle and Karen Armstrong. Budapest; Helsinki: Académiai Kiádo; The Finnish Literature Society. pp. 244–245. ISBN 978-9630578851. Translated from the Russian edition; Russian Academy of Sciences (1999).

Further reading

- Ermolov, A. S. (1905). Народная сельскохозяйственная мудрость в пословицах, поговорках и приметах [Folk agricultural wisdom in proverbs, sayings and signs]. Vol. 2. Всенародная агрономия . St Petersburg: Типография А. С. Суворина. p. 528. (Author: Ермолов А. С.).

- Ivanov, Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich (2007). Т. 4: Знаковые системы культуры, искусства и науки [Vol. 4: Sign Systems of Culture, Art and Science] (PDF). Избранные труды по семиотике и истории культуры. . Мoscow: Языки славянских культур. p. 792. ISBN 978-5-9551-0207-8. (Author: Иванов, Вячеслав Всеволодович).

- Maksimov, Sergey Vasilyevich (1903). "Параскева Пятница". Нечистая, неведомая и крестная сила (in Russian). St. Petersburg: R. Golike and A. Vilborg Publishing. pp. 516–518 – via Викитека .

- Author article on Russian-language Wikipedia: Максимов, Сергей Васильевич.

External links

- Параскева Пятница (hrono.ru)

- Параскева // Российский этнографический музей

- Пятница // Энциклопедия культур

- Успенский Б. А. Почитание Пятницы и Недели в связи с культом Мокоши // Успенский Б. А. Филологические разыскания в области славянских древностей

- Рыбаков Б. А. Двоеверие. Языческие обряды и празднества XI—XIII веков // Рыбаков Б. А. Язычество Древней Руси

- Страсти по Святой Параскеве (dralexmd.livejournal.com)

- Basil Lourié. Friday Veneration in the Sixth- and Seventh-Century Christianity and the Christian Legends on Conversion of Nağrān (англ.)