Pharmacognosy

In today's article we will explore the exciting world of Pharmacognosy. Whether we are talking about the life of a celebrity, a historical event, a social phenomenon or any other topic, there is certainly a lot to say about it. Throughout the next few lines we will delve into the most fascinating details of Pharmacognosy, analyzing its importance, its implications and its relevance in the corresponding field. From its impact on society to its role in popular culture, we will delve into a wide range of aspects that will allow us to better understand the magnitude of Pharmacognosy. We hope that this reading is as enriching as it is entertaining, and that it gives you a new perspective on Pharmacognosy. Get ready to embark on a journey of discovery and learning!

Pharmacognosy is the study of crude drugs obtained from medicinal plants, animals, fungi, and other natural sources.[1] The American Society of Pharmacognosy defines pharmacognosy as "the study of the physical, chemical, biochemical, and biological properties of drugs, drug substances, or potential drugs or drug substances of natural origin as well as the search for new drugs from natural sources".[2]

Description

The word "pharmacognosy" is derived from two Greek words: φάρμακον, pharmakon (drug), and γνῶσις gnosis (knowledge) or the Latin verb cognosco (con, 'with', and gnōscō, 'know'; itself a cognate of the Greek verb γι(γ)νώσκω, gi(g)nósko, meaning 'I know, perceive'),[3] meaning 'to conceptualize' or 'to recognize'.[4]

The term "pharmacognosy" was used for the first time by the German physician Johann Adam Schmidt (1759–1809) in his published book Lehrbuch der Materia Medica in 1811, and by Anotheus Seydler in 1815, in his Analecta Pharmacognostica.

Originally—during the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century—"pharmacognosy" was used to define the branch of medicine or commodity sciences (Warenkunde in German) which deals with drugs in their crude, or unprepared form. Crude drugs are the dried, unprepared material of plant, animal or mineral origin, used for medicine. The study of these materials under the name Pharmakognosie was first developed in German-speaking areas of Europe, while other language areas often used the older term materia medica taken from the works of Galen and Dioscorides. In German, the term Drogenkunde ("science of crude drugs") is also used synonymously.

As late as the beginning of the 20th century, the subject had developed mainly on the botanical side, being particularly concerned with the description and identification of drugs both in their whole state and in powder form. Such branches of pharmacognosy are still of fundamental importance, particularly for botanical products (widely available as dietary supplements in the U.S. and Canada), quality control purposes, pharmacopoeial protocols and related health regulatory frameworks. At the same time, development in other areas of research has enormously expanded the subject. The advent of the 21st century brought a renaissance of pharmacognosy, and its conventional botanical approach has been broadened up to molecular and metabolomic levels.[5]

In addition to the previously mentioned definition, the American Society of Pharmacognosy defines pharmacognosy as "the study of natural product molecules (typically secondary metabolites) that are useful for their medicinal, ecological, gustatory, or other functional properties."[6] Similarly, the mission of the Pharmacognosy Institute at the University of Illinois at Chicago involves plant-based and plant-related health products for the benefit of human health.[7] Other definitions are more encompassing, drawing on a broad spectrum of biological subjects, including botany, ethnobotany, marine biology, microbiology, herbal medicine, chemistry, biotechnology, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmaceutics, clinical pharmacy, and pharmacy practice.

- medical ethnobotany: the study of traditional uses of plants for medicinal purposes;

- ethnopharmacology: the study of pharmacological qualities of traditional medicinal substances;

- phytotherapy: the study of medicinal use of plant extracts;

- phytochemistry: the study of chemicals derived from plants (including the identification of new drug candidates derived from plant sources);

- zoopharmacognosy: the process by which animals self-medicate, by selecting and using plants, soils, and insects to treat and prevent disease;

- marine pharmacognosy: the study of chemicals derived from marine organisms.

Biological background

All plants produce chemical compounds as part of their normal metabolic activities. These phytochemicals are divided into (1) primary metabolites such as sugars and fats, which are found in all plants; and (2) secondary metabolites—compounds which are found in a smaller range of plants, serving more specific functions.[8] For example, some secondary metabolites are toxins used by plants to deter predation and others are pheromones used to attract insects for pollination. It is these secondary metabolites and pigments that can have therapeutic actions in humans and which can be refined to produce drugs—examples are inulin from the roots of dahlias, quinine from the cinchona, THC and CBD from the flowers of cannabis, morphine and codeine from the poppy, and digoxin from the foxglove.[8]

Plants synthesize a variety of phytochemicals, but most are derivatives:[9]

- Alkaloids are a class of chemical compounds containing a nitrogen ring. Alkaloids are produced by a large variety of organisms, including bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals, and are part of the group of natural products (also called secondary metabolites). Many alkaloids can be purified from crude extracts by acid-base extraction. Many alkaloids are toxic to other organisms.

- Polyphenols (a.k.a. phenolics) are compounds that contain phenol rings. The anthocyanins that give grapes their purple color, the isoflavones, the phytoestrogens from soy and the tannins that give tea its astringency are phenolics.

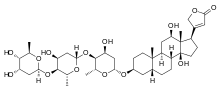

- Glycosides are molecules in which a sugar is bound to a non-carbohydrate moiety, usually a small organic molecule. Glycosides play numerous important roles in living organisms. Many plants store chemicals in the form of inactive glycosides. These can be activated by enzyme hydrolysis, which causes the sugar part to be broken off, making the chemical available for use.

- Terpenes are a large and diverse class of organic compounds, produced by a variety of plants, particularly conifers, which are often strong smelling and thus may have a protective function. They are the major components of resins, and of turpentine produced from resins. When terpenes are modified chemically, such as by oxidation or rearrangement of the carbon skeleton, the resulting compounds are generally referred to as terpenoids. Terpenes and terpenoids are the primary constituents of the essential oils of many types of plants and flowers. Essential oils are used widely as natural flavor additives for food, as fragrances in perfumery, and in traditional and alternative medicines such as aromatherapy. Synthetic variations and derivatives of natural terpenes and terpenoids also greatly expand the variety of aromas used in perfumery and flavors used in food additives. The fragrance of rose and lavender is due to monoterpenes. The carotenoids produce shades of red, yellow and orange in pumpkin, maize, and tomatoes.

Natural products chemistry

A typical protocol to isolate a pure chemical agent from natural origin is bioassay-guided fractionation, meaning step-by-step separation of extracted components based on differences in their physicochemical properties, and assessing the biological activity, followed by next round of separation and assaying. Typically, such work is initiated after a given crude drug formulation (typically prepared by solvent extraction of the natural material) is deemed "active" in a particular in vitro assay. If the end-goal of the work at hand is to identify which one(s) of the scores or hundreds of compounds are responsible for the observed in vitro activity, the path to that end is fairly straightforward:

- fractionate the crude extract, e.g. by solvent partitioning or chromatography.

- test the fractions thereby generated with in vitro assays.

- repeat steps 1) and 2) until pure, active compounds are obtained.

- determine structure(s) of active compound(s), typically by using spectroscopic methods.

In vitro activity does not necessarily translate to biological activity in humans or other living systems.

Herbal

In the past, in some countries in Asia and Africa, up to 80% of the population may rely on traditional medicine (including herbal medicine) for primary health care.[10] Native American cultures have also relied on traditional medicine such as ceremonial smoking of tobacco, potlatch ceremonies, and herbalism, to name a few, prior to European colonization.[11] Knowledge of traditional medicinal practices is disappearing in indigenous communities, particularly in the Amazon.[12][13][14]

With worldwide research into pharmacology as well as medicine, traditional medicines or ancient herbal medicines are often translated into modern remedies, such as the anti-malarial group of drugs called artemisinin isolated from Artemisia annua herb, a herb that was known in Chinese medicine to treat fever. However, it was found that its plant extracts had antimalarial activity, leading to the Nobel Prize winning discovery of artemisinin.[15][16]

Microscopical evaluation

Microscopic evaluation is essential for the initial identification of herbs, identifying small fragments of crude or powdered herbs, identifying adulterants (such as insects, animal feces, mold, fungi, etc.), and recognizing the plant by its characteristic tissue features. Techniques such as microscopic linear measurements, determination of leaf constants, and quantitative microscopy are also utilized in this evaluation. The determination of leaf constants includes stomatal number, stomatal index, vein islet number, vein termination number, and palisade ratio.[17]

The stomatal index is the percentage formed by the number of stomata divided by the total number of epidermal cells, with each stoma being counted as one cell.

where:

S.I. is the stomatal index

S is the number of stomata per unit area

E is the number of epidermal cells in the same unit area.[18]

See also

References

- ^ Fields, Deborah; Zoppi, Lois (2016-08-01). "What is Pharmacognosy?". News-Medical.net. Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- ^ The American Society of Pharmacognosy

- ^ Harrison, E. (November 1929). "Liddell and Scott, Part IV – A Greek-English Lexicon. Compiled by H. G. Liddell and R. Scott. A new edition … by H. Stuart Jones and R. Mckenzie. Part IV.: ⋯ξευτον⋯ω—θησαυριστικ⋯ς. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1929. Paper, 10s. 6d". The Classical Review. 43 (5): 189. doi:10.1017/s0009840x00053762. ISSN 0009-840X.

- ^ Franchi, Stefano; Bianchini, Francesco, eds. (2011-01-01). The Search for a Theory of Cognition. doi:10.1163/9789401207157. ISBN 9789401207157.

- ^ Dhami, N. (2013). "Trends in Pharmacognosy: A modern science of natural medicines". Journal of Herbal Medicine. 3 (4): 123–131. doi:10.1016/j.hermed.2013.06.001.

- ^ "About the ASP". American Society of Pharmacognosy.

- ^ "Pharmacognosy Institute".

- ^ a b Meskin, Mark S. (2002). Phytochemicals in Nutrition and Health. CRC Press. p. 123. ISBN 9781587160837 – via Google Books.

- ^ Springbob, Karen; Kutchan, Toni M. (2009). "Introduction to the different classes of natural products". In Lanzotti, Virginia (ed.). Plant-Derived Natural Products: Synthesis, Function, and Application. Springer. p. 3. ISBN 9780387854977 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Traditional Medicine". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on April 28, 2004. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ^ "Native American/Alaska Native Traditional Healing | aidsinfonet.org | The AIDS InfoNet". www.aidsinfonet.org. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- ^ Farnsworth, N. R. (1990). "The role of ethnopharmacology in drug development". Bioactive Compounds from Plants. Ciba Foundation Symposium 154. New York: Wiley Interscience.

- ^ Farnsworth NR (1988). "Screening plants for new medicines". In Wilson EO, Peters FM (eds.). Biodiversity. Washington DC: National Academy Press. pp. 83–97.

- ^ Balick, M. J. (1990). "Ethnobotany and the identification of therapeutic agents from the rainforest". Bioactive Compounds. Ciba Foundation Symposium 154. New York: Wiley Interscience. pp. 22–31.

- ^ "This Ancient Chinese Remedy Helped Win the Nobel Prize". Time. Retrieved 2021-10-11.

- ^ Su, Xin-zhuan; Miller, Louis H. (November 2015). "The discovery of artemisinin and Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine". Science China Life Sciences. 58 (11): 1175–1179. doi:10.1007/s11427-015-4948-7. ISSN 1674-7305. PMC 4966551. PMID 26481135.

- ^ Shah, Biren; Seth, Avinash (2012-05-14). Textbook of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-81-312-3260-6.

- ^ "Stomatal Index Calculator | Calculate Stomatal Index". www.calculatoratoz.com. Retrieved 2024-05-17.

External links

Media related to Pharmacognosy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pharmacognosy at Wikimedia Commons