Second presidency of Grover Cleveland

Nowadays, Second presidency of Grover Cleveland is a topic that has caught the attention of many people around the world. With the advancement of technology and unlimited access to information, Second presidency of Grover Cleveland has become a relevant topic in today's society. Whether due to its impact on health, its influence on human relationships or its importance in the economy, Second presidency of Grover Cleveland has become a topic of general interest. In this article, we will explore different aspects of Second presidency of Grover Cleveland and how it has come to the fore in the public conversation. From its origin to its future implications, there is no doubt that Second presidency of Grover Cleveland is a topic that deserves to be analyzed and understood in depth.

Portrait, 1892 | |

| Second presidency of Grover Cleveland March 4, 1893 – March 4, 1897 | |

Vice President | |

|---|---|

| Cabinet | See list |

| Party | Democratic |

| Election | 1892 |

| Seat | White House |

|

| |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

28th Governor of New York 22nd & 24th President of the United States Presidential campaigns  |

||

The second tenure of Grover Cleveland as the president of the United States began on March 4, 1893, when he was inaugurated as the nation's 24th president, and ended on March 4, 1897. Cleveland, a Democrat from New York, who previously served as president from 1885 to 1889, took office following his victory over Republican incumbent President Benjamin Harrison of Indiana in the 1892 presidential election. Cleveland was the first U.S. president to leave office after one term and later be elected for a second term.[a] He was succeeded by Republican William McKinley.

As his second term began, disaster hit the nation when the Panic of 1893 produced a severe national economic depression. Cleveland presided over the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, striking a blow against the Free Silver movement, and also lowered tariff rates by allowing the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act to become law. He also ordered federal soldiers to crush the Pullman Strike. In foreign policy, Cleveland resisted the annexation of Hawaii and an American intervention in Cuba. He also sought to uphold the Monroe Doctrine and forced Great Britain to agree to arbitrate a border dispute with Venezuela. In the midterm elections of 1894, Cleveland's Democratic Party suffered a massive defeat that opened the way for the agrarian and silverite seizure of the Democratic Party.

The 1896 Democratic National Convention repudiated Cleveland and nominated silverite William Jennings Bryan, but Bryan was defeated by Republican William McKinley in the subsequent election. Cleveland left office extremely unpopular, but his reputation was eventually rehabilitated in the 1930s by scholars led by Allan Nevins. More recent historians and biographers have taken a more ambivalent view of Cleveland, but many note Cleveland's role in re-asserting the power of the presidency. In rankings of American presidents by historians and political scientists, Cleveland is generally ranked as an average or above-average president.

Election of 1892

After his loss in the 1888 election, Cleveland returned to New York, where he resumed his legal career.[1] Cleveland established himself as a contender for the 1892 nomination with his February 1891 "Silver Letter," in which he deplored the rising strength of the Free Silver movement in the Democratic Party.[2] Cleveland's chief opponent for the nomination was David B. Hill, now a Senator for New York.[3] Hill united the anti-Cleveland elements of the Democratic party—silverites, protectionists, and Tammany Hall—but was unable to create a coalition large enough to deny Cleveland the nomination, and Cleveland was nominated on the first ballot of the convention.[4][3] For vice president, the Democrats chose to balance the ticket with Adlai Stevenson I of Illinois, a silverite.[5] Although the Cleveland forces preferred Isaac P. Gray of Indiana for vice president, they accepted the convention favorite.[6] As a supporter of greenbacks and Free Silver to inflate the currency and alleviate economic distress in the rural districts, Stevenson balanced the otherwise hard-money, gold-standard ticket headed by Cleveland.[7] The Republicans re-nominated President Harrison, making the 1892 election a rematch of the one four years earlier.

The issue of the tariff worked to the Republicans' advantage in 1888, but the legislative revisions of the past four years had made imported goods so expensive that many voters favored tariff reform and were skeptical of big business.[8] Many Westerners, traditionally Republican voters, defected to James Weaver, the candidate of the new Populist Party. Weaver promised Free Silver, generous veterans' pensions, and an eight-hour work day.[9] At the campaign's end, many Populists and labor supporters endorsed Cleveland after an attempt by the Carnegie Corporation to break the union during the Homestead Strike in Pittsburgh and after a similar conflict between big business and labor at the Tennessee Coal and Iron Co.[10] The Tammany Hall Democrats, meanwhile, adhered to the national ticket, allowing a united Democratic Party to carry New York.[11]

Cleveland won 46% of the popular vote and 62.4% of the electoral vote, becoming the first of only two Presidents to win non-consecutive presidential terms. Harrison won 43% of the popular vote and 32.7% of the electoral vote, while Weaver won 8.5% of the popular vote and the votes of several presidential electors from Western states.[12] Cleveland swept the Solid South, won the swing states of New York, New Jersey, Indiana, and Connecticut, and surprised many observers by also taking Illinois, Wisconsin, and Indiana.[13] In the concurrent congressional elections, Democrats retained control of the House and won control of the Senate, giving the party unified control of Congress and the presidency for the first time since the Civil War.[14] Cleveland's victory made him the second individual to win the popular vote in three presidential elections, alongside Andrew Jackson.[15][b]

Administration

Cleveland was sworn into office as the 24th president of the United States on March 4, 1893. That same day, Stevenson was sworn in as vice president.

Cabinet

Appointments

| The Second Cleveland cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Grover Cleveland | 1893–1897 |

| Vice President | Adlai Stevenson I | 1893–1897 |

| Secretary of State | Walter Q. Gresham | 1893–1895 |

| Richard Olney | 1895–1897 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | John G. Carlisle | 1893–1897 |

| Secretary of War | Daniel S. Lamont | 1893–1897 |

| Attorney General | Richard Olney | 1893–1895 |

| Judson Harmon | 1895–1897 | |

| Postmaster General | Wilson S. Bissell | 1893–1895 |

| William Lyne Wilson | 1895–1897 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Hilary A. Herbert | 1893–1897 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Hoke Smith | 1893–1896 |

| David R. Francis | 1896–1897 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Julius Sterling Morton | 1893–1897 |

Front row (left to right): Daniel S. Lamont, Richard Olney, Cleveland, John G. Carlisle, Judson Harmon.

Back row (left to right): David R. Francis, William L. Wilson, Hilary A. Herbert, Julius S. Morton.

In assembling his second cabinet, Cleveland avoided re-appointing the cabinet members of his first term. Two long-time Cleveland loyalists, Daniel S. Lamont and Wilson S. Bissell, joined the cabinet as Secretary of War and Postmaster General, respectively. Walter Q. Gresham, a former Republican who had served in President Arthur's cabinet, became Secretary of State. Richard Olney of Massachusetts was appointed as Attorney General, and he succeeded Gresham as Secretary of State after the latter's death. Former Speaker of the House John G. Carlisle of Kentucky became the Secretary of the Treasury.[16]

Cancer

In 1893, Cleveland underwent oral surgery to remove a tumor. Cleveland decided to have surgery secretly, to avoid further panic that might worsen the financial depression.[17] The surgery occurred on July 1, to give Cleveland time to make a full recovery in time for the upcoming Congressional session.[18] The surgeons operated aboard the Oneida, a yacht owned by Cleveland's friend E. C. Benedict, as it sailed off Long Island.[19] The surgery was conducted through the president's mouth, to avoid any scars or other signs of surgery.[20] The size of the tumor and the extent of the operation left Cleveland's mouth disfigured.[21] During another surgery, Cleveland was fitted with a hard rubber dental prosthesis that corrected his speech and restored his appearance.[21] A cover story about the removal of two bad teeth kept the suspicious press placated.[22] Cleveland's operation would not be revealed to the public until 1917.[23]

Economic panic and the silver issue

Shortly after Cleveland's second term began, the Panic of 1893 struck the stock market, and the Cleveland administration faced an acute economic depression.[24] The panic was sparked by the collapse of the overleveraged Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, but several underlying issues contributed to the start of a severe economic crisis. European credit played a major role in the U.S. economy during the Gilded Age, and European investors often infused cash into the economy. However, international investor confidence had been damaged by a financial crisis in Argentina, which had nearly caused the collapse of the London-based Barings Bank. Combined with poor economic conditions in Europe, the Argentinian financial crisis led many European investors to liquidate their American investments. Further exacerbating the economy was the poor cotton crop in the U.S. in 1892, as the export of cotton often infused the U.S. economy with European cash and credit. These factors combined to leave the U.S. financial system with insufficient financial resources, and, as the U.S. lacked a central banking system, the federal government had little control over the money supply.

One of the first clear signs of financial crisis came on February 20, 1893, twelve days prior to Cleveland's inauguration, when receivers were appointed for the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, which had greatly overextended itself.[25][26] President Harrison and United States Secretary of the Treasury Charles Foster ignored the urging of individuals such as J.P. Morgan to take steps to reassure investors.[27] Instead, Harrison reassured Congress that there was no cause for concern.[28] Thus the crisis was laid at Cleveland's feet. Republicans would ultimately go on to subsequently blame Cleveland for causing the economic downturn that he had, in actuality, inherited from the Republican Harrison.[29]

As panic spread following the collapse of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, a May 1893 bank run throughout the nation left the financial system with even less resources.[30] Cleveland believed that bimetallism encouraged the hoarding of gold[24] and discouraged investment from European financiers.[31] He argued that adopting the gold standard would alleviate the economic crisis by providing a hard currency.[24] Seeking to repeal the Sherman Silver Purchase Act and end the coinage of silver-based currency, Cleveland called a special session of Congress, to begin in August 1893.[32] The silverites rallied their following at a convention in Chicago, and the House of Representatives debated for fifteen weeks before passing the repeal by a considerable margin.[33] In the Senate, the repeal of silver coinage was equally contentious. Cleveland, forced against his better judgment to lobby the Congress for repeal, cajoled several Senate Democrats to support repeal.[34] Many Senate Democrats favored a middle course between the silverites and Cleveland, but Cleveland squashed their attempts to produce a compromise bill.[32] A combination of Democrats and eastern Republicans ultimately supported the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, and the repeal bill passed the Senate by a 48–37 majority.[34] Depletion of the Treasury's gold reserves continued, at a lesser rate, but subsequent bond issues replenished supplies of gold.[35] At the time the repeal seemed a minor setback to silverites, but it marked the beginning of the end of silver as a basis for American currency.[36]

Contrary to the administration's claims during the debate over the repeal bill, the repeal failed to restore investor confidence.[37] Hundreds of banks and other businesses failed, and 25 percent of the nation's railroads were in receivership by 1895.[38] Unemployment rates rose above 20 percent in much of the country, while those who were able to remain employed experienced significant wage cuts.[39] The economic panic also caused a drastic reduction in government revenue. In 1894, with the government in danger of being unable to meet its expenditures, Cleveland convinced a group led by financier J. P. Morgan to purchase sixty million dollars in U.S. bonds. The deal resulted in an infusion of gold into the economy, allowing for the continuation of the gold standard, but Cleveland was widely criticized for relying on Wall Street bankers to keep the government running.[40] Poor economic conditions persisted throughout Cleveland's second term, and unemployment levels rose in late 1895 and 1896.[35]

Labor unrest

Coxey's Army

The Panic of 1893 damaged labor conditions across the United States, and the victory of anti-silver legislation worsened the mood of western laborers.[41] A group of workingmen led by Jacob S. Coxey began to march east toward Washington, D.C. to protest Cleveland's policies.[41] This group, known as Coxey's Army, agitated in favor of a national roadbuilding program to give jobs to workingmen, and a bimetallist currency to help farmers pay their debts.[41] The march began with just 122 participants, but, in a sign of its national prominence, was covered by 44 assigned reporters. Numerous individuals joined Coxey's Army along its route, and many who sought to join the march hijacked railroads. Upon arriving in Washington, the marchers were dispersed by the U.S. Army and then prosecuted for demonstrating in front of the United States Capitol. Coxey himself returned to Ohio to unsuccessfully run for Congress as a member of the Populist Party in the 1894 elections.[42] Though Coxey's Army did not present a serious threat to the government, it signaled a growing dissatisfaction in the West with Eastern monetary policies.[43]

Pullman Strike

As railroads suffered from declining profits, they cut wages to workers; by April 1894, the average railroad worker's pay had declined by over 25 percent since the start of 1893. Led by Eugene V. Debs, the American Railway Union (ARU) organized strikes against the Northern Pacific Railway and the Union Pacific Railroad. The strikes soon spread to other industries, including the Pullman Company. After George Pullman refused to negotiate with the ARU and laid off workers involved with the union, the ARU refused to service any railroad car constructed by the Pullman Company, beginning the Pullman Strike.[44] By June 1894, 125,000 railroad workers were on strike, paralyzing the nation's commerce.[45] Because the railroads carried the mail, and because several of the affected lines were in federal receivership, Cleveland believed a federal solution was appropriate.[46] He was urged to act by Attorney General Olney, a former railroad attorney who worked with railroad interests to destroy the ARU.[47]

Cleveland obtained an injunction in federal court, and when the strikers refused to obey it, he sent federal troops into Chicago and 20 other rail centers.[48] "If it takes the entire army and navy of the United States to deliver a postcard in Chicago", he proclaimed, "that card will be delivered."[49] Governor John P. Altgeld of Illinois angrily protested Cleveland's deployment of troops, arguing that Cleveland had usurped the police power of state governments.[50] Though Rutherford B. Hayes had set a precedent for using federal soldiers in labor disputes, Cleveland was the first president to deploy soldiers in a labor dispute without the invitation of a state governor.[50] Leading newspapers of both parties applauded Cleveland's actions, but the use of troops hardened the attitude of organized labor toward his administration.[51] Cleveland's actions would be upheld by the Supreme Court in the case of In re Debs, which sanctioned the president's right to intervene in labor disputes that affected interstate commerce.[52] The outcome of the Pullman Strike, combined with the administration's weak anti-trust prosecution against the American Sugar Refining Company, made many believe that Cleveland was a tool of big business.[53]

Tariff frustrations

The McKinley Tariff was the centerpiece of Republican policy, but Democrats attacked it for raising consumer prices.[54] Democrats believed their victory in the 1892 election gave them a mandate to lower tariff rates, and Democratic leaders made tariff reduction a key priority after Congress repealed the Sherman Silver Act.[55] West Virginian Representative William L. Wilson introduced a tariff reduction bill, co-written with Cleveland administration, in December 1893.[56] The bill proposed moderate downward revisions in the tariff, especially on raw materials.[57] The shortfall in revenue was to be made up by an income tax of two percent on income above $4,000,[57] equivalent to $140,000 today[58]. Corporate profits, gifts, and inheritances would also be taxed at a two percent rate.[59] The bill would restore the federal income tax for the first time since the 1870s; supporters of the income tax believed that it would help reduce income inequality and shift the burden of taxation to the wealthy.[60] Wilson and the Cleveland administration were ambivalent about the income tax, but it was included in the bill due to the efforts of Congressmen William Jennings Bryan and Benton McMillin.[61] After lengthy debate, the bill passed the House by a considerable margin.[62]

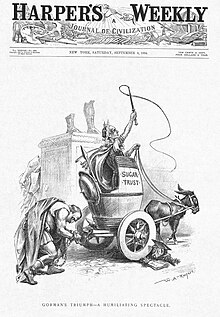

The bill was next considered in the Senate, where it faced stronger opposition from key Democrats led by Arthur Pue Gorman of Maryland, who insisted on more protection for their states' industries than the Wilson bill allowed.[63] The bill passed the Senate with more than 600 amendments attached that nullified most of the reforms. The Sugar Trust in particular lobbied for changes that favored it at the expense of the consumer.[64] Despite strong conservative opposition to the income tax, it remained in the bill, partly because many senators believed that the Supreme Court would eventually declare the tax to be unconstitutional.[65] After extensive debate, the Senate passed the Wilson–Gorman tariff bill in July 1894 in a 39-to-34 vote.[66] Wilson and Cleveland attempted to restore some of lower rates of the original House bill, but the House voted to enact the Senate version of the bill in August 1894.[67] The final bill lowered average tariff rates from 49 percent to 42 percent.[66] Cleveland was outraged with the final bill and denounced it as a disgraceful product of the control of the Senate by trusts and business interests. His main issue was thus ruined. Even so, he believed that the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act was an improvement over the McKinley tariff and allowed it to become law without his signature.[68] The personal income tax included in the tariff was struck down by the Supreme Court in the 1895 case, Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.[69]

Civil rights

In 1892, Cleveland had campaigned against the Lodge Bill,[71] which would have strengthened voting rights protections through the appointing of federal supervisors of congressional elections upon a petition from the citizens of any district. Once in office, he continued to oppose any federal effort to protect voting rights. The Enforcement Act of 1871 provided for a detailed federal overseeing of the electoral process, from registration to the certification of returns, but in 1894 Cleveland signed a repeal of this law.[72] Cleveland approved of the 1896 Supreme Court decision of Plessy v. Ferguson, which recognized the constitutionality of racial segregation under the "separate but equal" doctrine.[73][c] With the Supreme Court and the federal government both unwilling to intervene to protect the suffrage of African-Americans, Southern states continued to pass numerous Jim Crow laws, effectively denying suffrage to many African Americans through a combination of poll taxes, literacy and comprehension tests, and residency and record-keeping requirements.[74][73]

1894 midterm elections

Just before the 1894 election, Cleveland was warned by Francis Lynde Stetson, an advisor:

We are on the eve of very dark night, unless a return of commercial prosperity relieves popular discontent with what they believe Democratic incompetence to make laws, and consequently with Democratic Administrations anywhere and everywhere.[75]

The warning was appropriate, for in the Congressional elections, Republicans won their biggest landslide in decades, taking full control of the House. Democrats experienced losses everywhere outside of the South, where the party fended off the Populist challenge to their dominance. The Populists increased their share of the national vote but lost control of Western states such as Kansas and Colorado to the Republicans.[76] Cleveland's factional enemies gained control of the Democratic Party in state after state, including full control in Illinois and Michigan, and made major gains in Ohio, Indiana, Iowa and other states. Wisconsin and Massachusetts were two of the few states that remained under the control of Cleveland's allies. The Democratic opposition were close to controlling two-thirds of the vote at the 1896 national convention, which they needed to nominate their own candidate.[77] For the last two years of his term, Cleveland faced a Republican-controlled Congress, and the remaining Democrats in Congress consisted largely of agrarian-oriented Southerners who held little allegiance to Cleveland.[78]

Foreign policy

| I suppose that right and justice should determine the path to be followed in treating this subject. If national honesty is to be disregarded and a desire for territorial expansion or dissatisfaction with a form of government not our own ought to regulate our conduct, I have entirely misapprehended the mission and character of our government and the behavior which the conscience of the people demands of their public servants. |

| -- Cleveland's message to Congress on the Hawaiian question, December 18, 1893.[79] |

When Cleveland re-entered office, he faced the question of Hawaiian annexation. In his first term, he had supported free trade with Hawai'i and accepted an amendment that gave the United States a coaling and naval station in Pearl Harbor.[80] In the intervening four years, Honolulu businessmen of European and American ancestry had denounced Queen Liliuokalani as a tyrant who rejected constitutional government. In early 1893 they engineered the overthrow of the monarchy, set up a republic under Sanford B. Dole, and sought to join the United States. The Harrison administration quickly agreed with representatives of the new government on a treaty of annexation, which was submitted it to the Senate for ratification on February 15, 1893.[81][82] On March 9, five days after taking office, Cleveland withdrew the treaty from the Senate. His biographer Alyn Brodsky argues it was a deeply personal opposition on Cleveland's part to what he saw as an immoral action against a little kingdom:

- Just as he stood up for the Samoan Islands against Germany because he opposed the conquest of a lesser state by a greater one, so did he stand up for the Hawaiian Islands against his own nation. He could have let the annexation of Hawaii move inexorably to its inevitable culmination. But he opted for confrontation, which he hated, as it was to him the only way a weak and defenseless people might retain their independence. It was not the idea of annexation that Grover Cleveland opposed, but the idea of annexation as a pretext for illicit territorial acquisition.[83]

Cleveland sent former congressman James Henderson Blount to Hawai'i to investigate the conditions there. Blount, a leader in the white supremacy movement in Georgia, had long denounced imperialism. Some observers speculated he would support annexation on grounds of the inability of Asiatics to govern themselves. Instead, Blount proposed that the U.S. military restore the Queen by force and argued that the Hawaiian natives should be allowed to continue their "Asiatic ways."[84] Cleveland decided to restore the queen, but she refused to grant amnesty as a condition of her reinstatement, saying that she would either execute or banish the current government in Honolulu, and seize all of their properties. Dole's government refused to yield their position, and few Americans wanted to use armed force to overthrow a republican government in order to install an absolute monarch. In December 1893, Cleveland referred the issue to Congress; he encouraged the continuation of the American tradition of non-intervention. Dole had more support in Congress than the queen.[85] Republicans warned that a completely independent Hawaii could not long survive the scramble for colonies. Most observers thought Japan would soon take it over, and indeed the population of Hawaii was already over 20 percent Japanese. The Japanese advance was worrisome especially on the West Coast.[86] The Senate, under Democratic control but opposed to Cleveland, commissioned the Morgan Report, which contradicted Blount's findings and found the overthrow was a completely internal affair.[87] Cleveland dropped all talk of reinstating the queen, and went on to recognize and maintain diplomatic relations with the new Republic of Hawaii. In 1898, after Cleveland left office, the United States annexed Hawaii.[88]

Closer to home, Cleveland adopted a broad interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine that not only prohibited new European colonies, but also declared an American national interest in any matter of substance within the Western Hemisphere.[89] When Britain and Venezuela disagreed over the boundary between Venezuela and the colony of British Guiana, Cleveland and Secretary of State Olney protested.[90] The British initially rejected the U.S. demand for an arbitration of the boundary dispute and rejected the validity and relevance of the Monroe Doctrine.[91] Ultimately, British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury decided that dispute over the boundary with Venezuela was not worth antagonizing the United States, and the British assented to arbitration.[92] A tribunal convened in Paris in 1898 to decide the matter, and in 1899 awarded the bulk of the disputed territory to British Guiana.[93] Seeking to extend arbitration to all disputes between the two countries, the United States and Britain agreed to the Olney–Pauncefote Treaty in 1897, but the treaty fell three votes short of ratification in the Senate.[94]

The Cuban War of Independence began late in 1895 as Cuban rebels sought to break free from Spanish rule. The United States and Cuba enjoyed close trade relations, and humanitarian concerns led many Americans to demand intervention on the side of the rebels. Cleveland did not sympathize with the rebel cause and feared that an independent Cuba would ultimately fall to another European power. He issued a proclamation of neutrality in June 1895 and warned that he would stop any attempted intervention by American adventurers.[95]

Military policy

The second Cleveland administration was as committed to military modernization as the first, and ordered the first ships of a navy capable of offensive action. Construction continued on the Endicott program of coastal fortifications begun under Cleveland's first administration.[96][97] The adoption of the Krag–Jørgensen rifle, the U.S. Army's first bolt-action repeating rifle, was finalized.[98][99] In 1895–96 Secretary of the Navy Hilary A. Herbert, having recently adopted the aggressive naval strategy advocated by Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, successfully proposed ordering five battleships (the Kearsarge and Illinois classes) and sixteen torpedo boats.[100][101] Completion of these ships nearly doubled the Navy's battleships and created a new torpedo boat force, which previously had only two boats. However, the battleships and seven of the torpedo boats were not completed until 1899–1901, after the Spanish–American War.[102]

Judicial appointments

Cleveland's trouble with the Senate hindered the success of his nominations to the Supreme Court in his second term. In 1893, after the death of Samuel Blatchford, Cleveland nominated William B. Hornblower to the Court.[103] Hornblower, the head of a New York City law firm, was thought to be a qualified appointee, but his campaign against a New York machine politician had made Senator David B. Hill his enemy.[103] Further, Cleveland had not consulted the Senators before naming his appointee, leaving many who were already opposed to Cleveland on other grounds even more aggrieved.[103] The Senate rejected Hornblower's nomination on January 15, 1894, by a vote of 30 to 24.[103]

Cleveland continued to defy the Senate by next nominating Wheeler Hazard Peckham, another New York attorney who had opposed Hill's machine.[104] Hill used all of his influence to block Peckham's confirmation, and on February 16, 1894, the Senate rejected the nomination by a vote of 32 to 41.[104] Reformers urged Cleveland to continue the fight against Hill and to nominate Frederic R. Coudert, but Cleveland acquiesced in an inoffensive choice, that of Senator Edward Douglass White of Louisiana, whose nomination was accepted unanimously.[104] Later, in 1896, another vacancy on the Court led Cleveland to consider Hornblower again, but he declined to be nominated.[105] Instead, Cleveland nominated Rufus Wheeler Peckham, the brother of Wheeler Hazard Peckham, and the Senate confirmed the second Peckham easily.[105]

States admitted to the Union

Midway through his second term, July 16, 1894, the 53rd United States Congress passed an act that permitted Utah to form a constitution and state government, and to apply for statehood.[106] On January 4, 1896, Cleveland proclaimed Utah a state on an equal footing with the other states of the Union.[107]

Election of 1896

Cleveland attempted to counteract the growing strength of the Free Silver movement, but Southern Democrats joined with their Western allies in rejecting Cleveland's economic policies.[108] The Panic of 1893 had destroyed Cleveland's popularity, even within his own party.[109] Though Cleveland never publicly announced that he would not seek re-election, he had no intention of running for a third term. Cleveland's silence on a potential successor was damaging to his faction of the party, as Cleveland's conservative allies were unable to unify behind one candidate.[110] Cleveland's agrarian and silverite enemies won control of the Democratic National Convention, repudiated Cleveland's administration and the gold standard, and nominated William Jennings Bryan on a Silver Platform.[111][112] Cleveland silently supported the Gold Democrats' third-party ticket that promised to defend the gold standard, limit government, and oppose high tariffs, but he declined the splinter group's offer to run for a third term.[113]

The 1896 Republican National Convention nominated former Governor William McKinley of Ohio. With the help of campaign manager Mark Hanna, McKinley had emerged as the front-runner for the nomination long before the convention by building the support of Republican leaders throughout the country.[114] In the general election, McKinley hoped to please both farmers and business interests by not taking a clear position on monetary issues.[115] He focused his campaign on attacking the Cleveland administration's handling of the economy, and argued that higher tariffs would restore prosperity.[116] Many Populist leaders wanted to nominate Eugene Debs and campaign on the party's full range of proposed reforms, but the 1896 Populist convention instead nominated Bryan.[117] Republicans portrayed Bryan and the Populists as social revolutionaries engaged in class warfare, while Bryan attacked McKinley as a tool of the rich.[118]

In the 1896 presidential election, McKinley won a decisive victory over Bryan, taking 51% of the popular vote and 60.6% of the electoral vote. Though Bryan had campaigned heavily in the Midwest, Democratic divisions and the traditional Republican strength in the area helped McKinley win a majority of the states in the region. McKinley also swept the Northeast, while Bryan swept the Solid South.[119] John Palmer, the candidate of the Gold Democrats, took just under one percent of the popular vote.[120] Despite Palmer's loss, Cleveland was pleased by the election outcome, as he strongly preferred McKinley to Bryan and saw the former's victory as vindication for the gold standard.[121]

Historical reputation

According to historian Henry Graff, Cleveland reasserted the power of the executive branch, but his lack of a clear vision for the country marked his presidency as pre-modern. Graff also notes that Cleveland helped establish Democratic dominance in the Solid South through policies of reconciliation, while at the same time revitalizing his party in the North by embracing civil service reform.[122] Historian Richard White describes Cleveland as the "Andrew Johnson" of the 1890s, in that Cleveland's temperament and policies were unsuited to the crisis confronting the nation.[123] Historian Richard Welch argues that Cleveland was successful in reasserting the power of the presidency, but lacked a broad vision for the country.[124]

Cleveland was one of the least popular public figures in the country when he left office in 1897, but his reputation had substantially recovered by the time of his death in 1908.[125] In A Study in Courage, a 1933 biography of Cleveland historian Allan Nevins portrayed Cleveland as a courageous reformer. Historians like Henry Steele Commager and Richard Hofstadter echoed this view, with Hofstadter writing that Cleveland was "the sole reasonable facsimile of a major president between Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt." Subsequent historians, however, emphasized Cleveland's failures and his favoritism towards big business. In a 1948 poll of historians, Cleveland was ranked as the eighth-greatest president in U.S. history, but his standing in polls of historians and political scientists has declined since 1948.[126] A 2018 poll of the American Political Science Association's Presidents and Executive Politics section ranked Cleveland as the 24th-best president.[127] A 2017 C-SPAN poll of historians ranked Cleveland as the 23rd-best president.[128]

Notes

- ^ Donald Trump became the second to do so following his win in the 2024 election.

- ^ Franklin D. Roosevelt would later win the popular vote in four presidential elections.

- ^ Plessy v. Ferguson would be overturned in the 1954 case of Brown v. Board of Education and subsequent rulings.

References

- ^ Graff, 98-99

- ^ Welch, 102–103

- ^ a b Nevins, 470–473

- ^ Tugwell, 182

- ^ Graff, 105; Nevins, 492–493

- ^ William DeGregorio, The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents, Gramercy 1997

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Art & History Home > Adlai Ewing Stevenson, 23rd Vice President (1893–1897)". Senate.gov. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ^ Nevins, 499

- ^ Graff, 106–107; Nevins, 505–506

- ^ Tugwell, 184–185

- ^ Graff, 108

- ^ Leip, David. "1892 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved February 22, 2008., "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved February 22, 2008.

- ^ Welch, 110–111

- ^ Graff, 109-110

- ^ Welch, 111

- ^ Graff, 113-114

- ^ Nevins, 528–529; Graff, 115–116

- ^ Nevins, 531–533

- ^ Nevins, 529

- ^ Nevins, 530–531

- ^ a b Nevins, 532–533

- ^ Nevins, 533; Graff, 116

- ^ Welch, 121

- ^ a b c Graff, 114

- ^ "IN RE RICE". Findlaw.

- ^ James L. Holton, The Reading Railroad: History of a Coal Age Empire, Vol. I: The Nineteenth Century, pp. 323–325, citing Vincent Corasso, The Morgans.

- ^ Millhiser, Ian (2021-01-14). "Abolish the lame-duck period". Vox. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Shafer, Ronald G. (28 December 2020). "Trump 2024? Only one president has returned to power after losing reelection". Washington Post. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Onion, Rebecca (2020-11-02). "What's the Worst a Vengeful Lame-Duck Administration Can Do?". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ White, pp. 766–772

- ^ White, p. 771

- ^ a b Welch, 117–119

- ^ Nevins, 524–528, 537–540. The vote was 239 to 108.

- ^ a b Tugwell, 192–195

- ^ a b Welch, 126–127

- ^ Timberlake, Richard H. (1993). Monetary Policy in the United States: An Intellectual and Institutional History. University of Chicago Press. p. 179. ISBN 0-226-80384-8.

- ^ Welch, 124

- ^ White, pp. 772–773

- ^ White, pp. 802–803

- ^ Graff, 114-115

- ^ a b c Graff, 117–118; Nevins, 603–605

- ^ White, pp. 806–807

- ^ Graff, 118; Jeffers, 280–281

- ^ White, pp. 781–784

- ^ Nevins, 614

- ^ Nevins, 614–618; Graff, 118–119; Jeffers, 296–297

- ^ Welch, 143–145

- ^ Nevins, 619–623; Jeffers, 298–302

- ^ Nevins, 628

- ^ a b Welch, 145

- ^ Nevins, 624–628; Jeffers, 304–305; Graff, 120

- ^ White, pp. 787–788

- ^ Graff, 120, 123

- ^ Graff, 100

- ^ Weisman, 120, 131

- ^ Welch, 131–132

- ^ a b Nevins, 564–566; Jeffers, 285–287

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Welch, 132–133

- ^ Weisman, 122–124, 137–139.

- ^ Weisman, 132–133

- ^ Nevins, 567; the vote was 204 to 140

- ^ Lambert, 213–15

- ^ Nevins, 577–578

- ^ Weisman, 144–145

- ^ a b Welch, 134–135

- ^ Welch, 135–137

- ^ Nevins, 564–588; Jeffers, 285–289

- ^ Graff, 117

- ^ Nevins, 568

- ^ James B. Hedges (1940), "North America", in William L. Langer, ed., An Encyclopedia of World History, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, Part V, Section G, Subsection 1c, p. 794.

- ^ Congressional Research Service (2004), The Constitution of the United States: Analysis and Interpretation—Analysis of Cases Decided by the Supreme Court of the United States to June 28, 2002, Washington: Government Printing Office, "Fifteenth Amendment", "Congressional Enforcement", "Federal Remedial Legislation", p. 2058.

- ^ a b "Grover Cleveland: A Powerful Advocate of White Supremacy". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. 31 (31): 53–54. Spring 2001. doi:10.2307/2679168. JSTOR 2679168.

- ^ Michael Perman.Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888–1908. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001, Introduction

- ^ Francis Lynde Stetson to Cleveland, October 7, 1894 in Allan Nevins, ed. Letters of Grover Cleveland, 1850–1908 (1933) p. 369

- ^ White, pp. 809–810

- ^ Richard J. Jensen, The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888–96 (1971) pp 229–230

- ^ Welch, 201–202

- ^ Nevins, 560

- ^ Zakaria, 80

- ^ Nevins, 549–552; Graff 121–122

- ^ Klotz, Robert J. (1997). "On the Way Out: Interregnum Presidential Activity" (PDF). Presidential Studies Quarterly. 27 (2): 320–332. JSTOR 27551733. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Alyn Brodsky (2000). Grover Cleveland: A Study in Character. Macmillan. p. 1. ISBN 9780312268831.

- ^ Tennant S. McWilliams, "James H. Blount, the South, and Hawaiian Annexation." Pacific Historical Review (1988) 57#1: 25-46 online.

- ^ Michael J. Gerhardt (2013). The Forgotten Presidents: Their Untold Constitutional Legacy. Oxford UP. pp. 171–72. ISBN 9780199967810.

- ^ William Michael Morgan, Pacific Gibraltar: U.S.-Japanese Rivalry Over the Annexation of Hawaii, 1885-1898 (2011).

- ^ Welch, 174

- ^ McWilliams, 25–36

- ^ Zakaria, 145–146

- ^ Graff, 123–125; Nevins, 633–642

- ^ Welch, 183–184

- ^ Welch, 186–187

- ^ Graff, 123–25

- ^ Welch, 192–194

- ^ Welch, 194–198

- ^ ?? Mark A. Berhow, American Seacoast Defenses A Reference Guide (1999) pp. 9–10

- ^ Endicott and Taft Boards at the Coast Defense Study Group website Archived 2016-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bruce N. Canfield "The Foreign Rifle: U.S. Krag–Jørgensen" American Rifleman October 2010 pp.86–89,126&129

- ^ Hanevik, Karl Egil (1998). Norske Militærgeværer etter 1867

- ^ Friedman, pp. 35–38

- ^ Bauer and Roberts, pp. 162–165

- ^ Bauer and Roberts, pp. 102–104, 162–165

- ^ a b c d Nevins, 569–570

- ^ a b c Nevins, 570–571

- ^ a b Nevins, 572

- ^ Timberlake, Richard H. (1993). Monetary Policy in the United States: An Intellectual and Institutional History. University of Chicago Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-226-80384-8.

- ^ Thatcher, Linda Thatcher (2016). "Struggle For Statehood Chronology". historytogo.utah.gov. State of Utah.

- ^ Welch, 202–204

- ^ White, pp. 836–837

- ^ Welch, 207–211

- ^ Nevins, 684–693

- ^ R. Hal Williams, Years of Decision: American Politics in the 1890s (1993)

- ^ Graff, 128–129

- ^ White, pp. 836–839

- ^ Graff, 126–127

- ^ White, pp. 837–841

- ^ White, pp. 843–844

- ^ White, pp. 845–846

- ^ White, pp. 847–851

- ^ Leip, David. "1896 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved February 23, 2008.

- ^ Graff, 129

- ^ Graff, Henry F. (4 October 2016). "GROVER CLEVELAND: IMPACT AND LEGACY". Miller Center. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ White, pp. 800–801

- ^ Welch, 219–221

- ^ Welch, 223

- ^ Welch, 4–6

- ^ Rottinghaus, Brandon; Vaughn, Justin S. (19 February 2018). "How Does Trump Stack Up Against the Best — and Worst — Presidents?". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ "Presidential Historians Survey 2017". C-SPAN. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

External links

Letters and speeches

- Text of a number of Cleveland's speeches at the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- Finding Aid to the Grover Cleveland Manuscripts, 1867–1908 at the New York State Library, accessed May 11, 2016

- 10 letters written by Grover Cleveland in 1884–86

Media coverage

- Second presidency of Grover Cleveland collected news and commentary at The New York Times

Other

- Grover Cleveland: A Resource Guide, Library of Congress

- Grover Cleveland: A bibliography by The Buffalo History Museum

- Grover Cleveland Sites in Buffalo, NY: A Google Map developed by The Buffalo History Museum

- Index to the Grover Cleveland Papers at the Library of Congress

- Essay on Cleveland and each member of his cabinet and First Lady, Miller Center of Public Affairs

- "Life Portrait of Grover Cleveland", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, August 13, 1999

- Interview with H. Paul Jeffers on An Honest President: The Life and Presidencies of Grover Cleveland, Booknotes (2000)

- Works by Grover Cleveland at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Grover Cleveland at the Internet Archive