UA3 experiment

In today's world, UA3 experiment is an issue that has gained great relevance in society. With the advancement of technology and globalization, UA3 experiment has become a question of interest to many people in different fields. Whether on a personal, professional, political or cultural level, UA3 experiment has generated debates and discussions around the world. In this article, we will deeply explore the topic of UA3 experiment, analyzing its different aspects and its impact on today's society. Additionally, we will examine how UA3 experiment has evolved over time and what challenges and opportunities it presents in the future.

| |

| Key SppS Experiments | |

|---|---|

| UA1 | Underground Area 1 |

| UA2 | Underground Area 2 |

| UA4 | Underground Area 4 |

| UA5 | Underground Area 5 |

| SppS pre-accelerators | |

| PS | Proton Synchrotron |

| AA | Antiproton Accumulator |

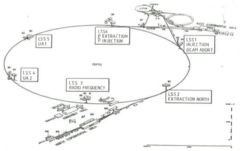

The Underground Area 3 (UA3) experiment was a high-energy physics experiment at the Proton-Antiproton Collider (SppS), a modification of the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS), at CERN. The experiment ran from 1978 to 1988 with the objective of searching for magnetic monopoles.[1] No evidence for magnetic monopoles was found by the UA3 experiment.[2]

The experiment shares the same intersection region used as the UA1 colliding experiment, and looked for expected high ionisation of magnetic monopole in plastic detectors.[3] The beam pipe was a stainless steel corrugated cylinder, with 0.2 mm thickness.[4]

Plastic detectors were used as they are best suited to the chemically etched tracks left by the ionising particles, and they resist high temperatures during baking.[5][4] The plastic detectors used were 125μm thick kapton foils. The foils were placed inside of the vacuum chamber and around the central track detector for the UA1.[6] Three cylindrical and four transverse layers of detectors were placed between three chambers: two forward chambers and a central chamber. This covered the maximum solid angle possible.[5]

Holes etched along a monopole track were determined using diffusion of a gas or dye through the holes, followed by a chemical reaction. The ionisation rates of magnetic monopoles were predicted to be very high due to their short range.[5]

See also

External links

References

- ^ "Greybook". greybook.cern.ch. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ Dowell, John D (1985). "Proton antiproton physics". CERN. doi:10.5170/CERN-1985-011.1.

- ^ Price, Michael J. (1984), Stone, James L. (ed.), "Experimental Searches for Magnetic Monopoles at Particle Colliders", Monopole ’83, NATO ASI Series, vol. 111, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 621–624, doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-0375-7_61, ISBN 978-1-4757-0375-7, retrieved 2023-08-03

- ^ a b Aubert, B.; Musset, P.; Price, M.; Vialle, J.P. (12 Oct 1982). "Search for magnetic monopoles in proton-antiproton interactions at 540 GeV cm energy". Physics Letters B. 120 (4–6): 465–467. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(83)90488-4.

- ^ a b c Aubert, B; Musset, P; Price, M; Vialle, J P (2 Feb 1978). "Search for Magnetic Monopoles" (PDF). Proposal to the SPSC.

- ^ Dowell, J D (1983). "Physics Results from the CERN Proton-Antiproton Collider" (PDF). Department of Physics, University of Birmingham, England.